We do not live in a virtual world. Our society is physical; it rests on the metals, alloys, minerals, glass, concrete, plastics, and chemicals that frame our skyscrapers, launch our satellites, mold our smartphones, design our food and medicine, and transport electricity and water to our homes.

This basic fact defines the critical geostrategic question of this century. In 2025, it is the People’s Republic of China that is far and away the leading producer of these physical commodities that undergird modernity. For example, China mines around 70 percent of the world’s rare earth metals necessary for advanced energy production, smartphones, aircraft, and other critical technologies.1 No advanced economy operates without China’s plants, factories, and mines. This is notably so for America, whose reliance on China is not limited to metals and alloys; China also provides over half of the upstream inputs needed to supply America’s hospitals and pharmacies.2

But China enjoys an even greater lead in the process technologies needed to refine and process commodities, and it aims to leverage this process mastery to capture the growth industries of the future. China’s 70-percent share of global rare earths supports its similarly dominant share of the world’s electric vehicle and battery production.3 In medicine, China not only produces America’s pharmaceutical inputs, it also controls the supply chains for America’s medical equipment, such as gauze, gowns, needles, syringes, catheters, and nitrile gloves.4 These production capabilities overlap: nitrile gloves are required to process rare earths, for instance. China’s manufacturing capabilities are self-reinforcing ecosystems that accumulate cross-sectoral tacit knowledge that will drive the development of drones, autonomous vehicles, industrial robots, semiconductors, sensors, optics, and other dual-use advanced technologies.

This tacit knowledge places a high barrier to entry for foreign competitors. But the manufacturing processes and associated intellectual property (IP) to refine and process commodities are themselves a major hurdle for new entrants. They are complex, financially costly, environmentally toxic, and produce small profit margins. And America cannot sustain its economy without them.

It should be no surprise that China is now flexing its dominance of commodity process technologies. Last week, China announced restrictions on the export of Chinese rare earth commodities, the technology to refine and process these rare earths, and the technology to produce the necessary equipment to mine, manufacture, refine, and process rare earths.5

China knows that process technologies are a necessary element of a strong economy. Chinese leaders are no doubt aware of nascent American efforts to rekindle industrialization. China does not want competition, and its leaders believe that America is so dependent on its commodities that American business interests will force President Trump to heel. In a People’s Daily op-ed published in advance of the rare earth export controls, “Zhong Caiwen,” widely believed to be the pseudonym for Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng, observed that China’s economic strategy is not “influenced by any special interest groups.”6 America, in contrast, is subject to a political environment that prevents its leaders from prioritizing “long-term and strategic considerations” and that instead shackles the nation to the whims of “short-term or local interests.”

So, what has China done with its ability to act on “long term-term and strategic considerations”? It has undertaken a multi-decade effort to conduct corporate espionage, steal and deploy foreign IP, force technology transfers, subsidize favored companies, flood global markets with underpriced goods and commodities, manipulate its currency, and now threatens to freeze vital supply chains. These are not the strategic actions of a friendly state or even a state seeking a balanced co-existence. Indeed, the Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party described China’s rare earth export controls as an “economic declaration of war.”7

Wartime situations require wartime solutions. If America’s leaders believe that China’s export restrictions amount to “economic war,” they should respond in kind. They should look to laws drafted when America faced similar adversaries during World War 1 and World War 2. Like its 20th century predecessors, Congress should empower the President to both seize the manufacturing and refining process technologies of malign and adversarial actors and repurpose this technology to drive reindustrialization.

China’s rare earth export controls demonstrate that our adversaries can and will cut off vital supply chains at a moment’s notice. We do not have time for Congressional funding or Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants that may or may not lead to factory-ready items or processes in five, ten, or fifteen years. Instead, we should put our adversaries on notice: if you steal our IP or make use of our stolen IP then we will come for your IP, processes, and know-how. We will seize it, wrestle it from your databases, wrench it from your machines, and bribe your employees and investors to siphon it from your facilities. We will award this IP to American companies, who will use it to protect our citizens, defend our homeland, and build the physical goods we need to make sure that you can never cut off the lifeblood of our economy.

We call this gambit “Dark SBIR.”

Dark SBIR - An Introduction

We are not the first Americans to face adversaries that weaponize critical supply chains. Before WW1, Imperial Germany cultivated dependencies in Great Britain and America, including chemical and pharmaceutical input and supply dependences. Germany sought to use these dependencies to extract concessions in peacetime and wartime, until American leaders fought back. The United States countered its adversary’s strategy by seizing and distributing German chemical and pharmaceutical input and process technologies, equipment, and assets, which helped develop America’s nascent pharmaceutical industry into a premier global sector. America again seized German (and Japanese) IP, equipment, and assets during WW2, and deployed these seized items to research, finance, and produce defense and industrial material.

These IP seizure authorities remain on the books, albeit with limited scope. The President may now only seize the IP, equipment, and assets of foreign adversaries during periods of war as declared by Congress. This may be a laudable limitation of federal power, but it comes at a major cost. The reality is that America’s present industrial capacity is significantly diminished in comparison to its prewar capacity. Putting aside America’s limited ability to mine metals, alloys, and minerals, America will struggle during a conflict to manufacture and refine these commodities. As a separate DARC author noted, “Chinese suppliers of rare earth products have masterfully manipulated supply and pricing in the last 30 years, all while driving erstwhile competitors in the U.S. and Europe out of the market. Chinese firms have also locked in feedstock suppliers worldwide through long term offtake agreements and invested in processing of minerals with high codependence/coproduction, making for multiple profitable revenue streams (ex. recovering high concentrations of Gallium via the production of alumina from mined bauxite).”8 America will similarly struggle to retool its existing plants and factories because it has largely lost the tacit knowledge and in-house process expertise that it enjoyed in the last century. We must wait for a formal declaration of war before addressing the real consequences of an ongoing economic war.

DARC readers will be familiar with this problem: America must close the industrial gap, and soon. Until it does, China can credibly threaten to strangle key economic sectors and exhaust America’s material reserves during a conflict.9

American political leaders can close the gap by seizing and deploying China’s world-leading process technologies. Industrialists and financiers are already working to reforge America’s industrial capacity. But these efforts are diffuse, costly, subject to unforgiving market forces, and hampered by compliance requirements and administrative and legislative vetoes. Too slow.

The federally-sanctioned commandeering and distribution of adversarial IP would inject nitrous into American reindustrialization. Investors and industrialists would spend less time playing catch up and instead focus on truly groundbreaking innovation. Manufacturers would enjoy liability shields when implementing best-in-class Chinese processes without fear of lengthy and costly legal battles. Speed is key. Congress should seize the initiative, disrupt our adversaries, and ensure that we can credibly deter China and maintain national security in a future conflict.

Dark SBIR is indeed an additional step in the economic decoupling of the United States and China, and should be made in recognition of drawbacks. First, there will be concern that infringement upon Chinese IP may be wrong either on principle or because of a fear of retaliatory escalation. Some believe that IP protections are a sacrosanct guarantor of innovation, wealth, and liberty. We need only look to China’s rapid economic and technological gains to dispel the notion that inviolable IP rights are a prerequisite for innovation.

As for an escalatory spiral, China’s rare earth export controls reveal a willingness to control and sever supply chains for items as commonplace as laptops and smartphones, which amounts to a blockade of fundamental aspects of America’s economy and American social activity. And China will not stop with rare earths, it will no doubt threaten to restrict any other choke point it can identify in an attempt to force political concessions. The political escalation has begun. In terms of legal escalation, Dark SBIR is an escalatory step, but not as radical as it might appear.

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. ch. 35) (IEEPA) and Section 721 of the Defense Production Act of 1950 already authorize the President to subject Chinese-owned private businesses in America or private American businesses that receive Chinese investment to implement various practices in the name of national security, such as conditioning foreign ownership on the divestment of product lines, mandating that the private company implement specific cybersecurity practices, and dictating restrictions on foreign investor access to that private company’s confidential information.10

While these authorities stop short of authorizing the full seizure and distribution of foreign-owned IP, the U.S. already limits foreign business rights in the interest of national security. Dark SBIR is no doubt a break with recent decades, but those decades resulted in precisely the problem we must now solve. Finally, one may be concerned that escalation will result in the Chinese stealing our IP; they do this already, or that it will result in the Chinese ramping up IP theft. They may increase their efforts if we implement Dark SBIR. They may increase their efforts even if we do not implement Dark SBIR. The fact remains that we do not have the world’s leading process manufacturing technologies for the low-margin commodities that power modernity, and they do. We must close the gap.

Second, there is a valid concern as to the timing of Dark SBIR. It would not be impossible for China to remove IP from any U.S. based servers or cloud infrastructure, so moves to seize such IP must be swift and secretive. But China is unlikely to be able to similarly diminish the U.S.’ ability to bribe engineers and factory workers or utilize intelligence agencies and private bounty hunters to acquire Chinese IP, and much of the valuable manufacturing process technology falls into this latter category. Indeed, while the millions of engineering students that China produces each year can be seen as a strength, it is also a vulnerability; each student offers an opportunity for America to offer fortune and citizenship in exchange for equipment and hard drives.11

Dark SBIR - Statutory Authorities

Dark SBIR is nested in the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 (50 U.S.C. chapter 53) (TWEA). TWEA was born during World War I as the culmination of pre-war and wartime legislation that authorized the President to seize and distribute foreign IP. Current TWEA authorities are only available following a Congressional declaration of war. Make no mistake, TWEA will be used during a time of war. That temporal distinction may have been sufficient when 20th-century America could quickly retool its vast manufacturing base. But today, waiting for a declaration of war is tantamount to accepting defeat. Facilities take time to build out. Lines take time to spin up. And our wartime ability to access, sequester, and deploy enemy technology is likely to be severely diminished.

Congress should not force the President to sit on the sidelines while our adversaries isolate America and its allies from foundational industrial process technologies. Our adversaries do not wait. Neither did the Americans that won two World Wars and delivered 50-years of American growth. And Congress need not radically overhaul TWEA. The President does not require carte blanche authority over all IP to level the playing field.

Current TWEA authorities allow the President to seize IP from specific categories of foreign individuals and entities, mainly enemies of the United States, defined to mean four main groups:

-

individuals or entities located in or incorporated in a nation at war with the United States;

-

governments of nations at war with the United States;

-

individuals that are natives, citizens, or subjects of any nation at war with the United States; and

-

the above categories of individuals, entities, or governments of an ally of a nation at war with the United States.

Congress should add a fifth category: IP thieves and other malign actors that actively degrade America’s national security and harm American citizens. This new category would empower the President to punish individuals or companies who demonstrably steal American R&D, violate U.S. sanctions, or otherwise commit harmful activities against the United States or American citizens. The President can then structure the distribution of seized IP to ensure it is deployed efficiently and effectively.

Congressional action may not even be required. A maximally aggressive counsel could argue that TWEA allows the President to presently seize Chinese IP because of the PRC’s relationship with North Korea. This argument rests on TWEA’s definition of war. TWEA defines “the beginning of the war” to mean when “Congress has declared or shall declare war or the existence of a state of war.” (emphasis added).

The argument proceeds as follows. First, while Congress never issued a formal declaration of war against North Korea, it “declared,” or at least acknowledged, the existence of a state of war by taking numerous actions to support U.S. and allied forces, including implementing a draft, establishing wage and price controls, passing the Defense Production Act of 1950 to mobilize America’s defense industrial base, funding military campaigns, and providing defense and economic aid to South Korea. Second, this state of war has not ended because the Korean War has not formally ended, because U.S. military presence in South Korea has not ended, and because North Korea has not stopped conducting malign activities against the United States and its citizens, critical infrastructure, IP, and financial assets, such as North Korea’s consistent cyber efforts to infiltrate America’s leading technology companies.12 Third, the PRC is a formal ally of North Korea and has materially aided North Korea’s efforts to arm its military, evade U.S. economic sanctions, and harm U.S. interests. Finally, therefore, PRC individuals and entities are subject to TWEA IP seizure authorities because the PRC is the ally of a nation with which Congress has acknowledged the existence of a state of war. (This analysis would also apply to other formal North Korea allies, such as the Russian Federation with its use of North Korean soldiers in Ukraine).

However, this would require a significant departure from existing jurisprudence, in which courts have previously declined to consider the Korean War a formal conflict. The Supreme Court notably declined to do so in the landmark and oft-cited executive branch foreign affairs powers case Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer 343 U.S. 579 (1952). Hopefully, China’s latest moves in the global market for rare earths should supply all the rationale needed for Congress to provide a clear authorization.

Recommendations

1. Congress should authorize the President to use TWEA authorities against proven IP thieves and designated malign actors.

Congress should reform TWEA authorities to quickly close the industrial gap and strike back at those that spent decades stealing American and allied know-how. At base, Congress should allow the President to designate and subject to TWEA entities determined to have stolen or aided in the theft of U.S. corporate and government intellectual property. The President could then sequester all IP and assets of these entities based in the United States, either from company branches, subsidiaries, or bank accounts, or hosted on U.S.-based servers.

TWEA’s new “IP thief” category should also be expanded to cover companies determined by the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to have been the direct beneficiaries of unfair trade practices (particularly espionage) pursuant to Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 investigation authorities in order to better reflect the nature of nation-state espionage. The category should also incorporate by reference other lists of entities and individuals determined to be malign actors, such as lists of restricted parties maintained by the Office of Foreign Assets Controls and the Bureau of Industry and Security. For an even broader approach the IP thief category should include companies determined by the U.S. government to use the IP stolen by the above entities, or that utilize slave labor or engage in human rights violation. Finally, the list should include subsidiaries and assets owned 50 percent of more, directly or indirectly, or materially controlled by, the above entities.

2. The President should source information from the business community, intelligence agencies, U.S. allies and partners, and freelance bounty hunters to designate entities as IP thieves.

The President should direct the Department of Commerce to establish channels for businesses to submit proof of theft and information on the identity of thieves and the identity of companies deploying or benefitting from the deployment of stolen IP. Commerce should work with intelligence agencies to confirm IP theft designations or support new designations. Additionally, the U.S. government should coordinate with trusted allies and partners such as the Five Eyes nations, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to identify multinational instances of IP theft and adjust designations and penalties accordingly.

The U.S. government must it clear to American business that if they can show (1) that a Chinese company has benefited from stolen IP; and (2) that company uses leading processes to churn out rare earth magnets, bearing-grade steel, engineering polymers, die casting, sheet metal cutting and forming, precision CNC machines, or any other technology needed to reindustrialize America; then (3) the United States will punish that company and its processes to seizure and distribution. The United States must then balance this information gathering campaign with a bounty program that awards individuals that obtain these processes from designated adversarial IP thieves.

3. The President should structure distribution of seized IP to maximize the speed of American reindustrialization.

After commandeering adversarial IP, the U.S. government should work to allocate IP to American firms based on their concrete and demonstrated abilities to intake, deploy, and scale the technology. Because time is short, the President should take care to ensure this process is not marred by cronysim, captured by current market leaders, or bogged down by efforts to satiate political allies with equitable dispensation across key congressional districts. But it is easier to achieve this with Dark SBIR than with Congressional grants. Perhaps the key characteristic of IP is that it is non-exclusive: more than one person can access, use, and derive value from IP at the same time. In contrast, exclusivity is the key feature of Congressional funding. Stroll down K Street and you will see the masters of this exclusivity in practice.

TWEA allows the U.S. government to wield the non-exclusivity principle with maximum effect. 50 U.S.C. 4310 provides the President broad authority to design award qualifications and structure license conditions for the distribution of seized IP. There are no FAR requirements here. The President should take advantage of this flexibility to build out different pathways based on the nature of the seized IP:

-

Award Non-Exclusive Licenses to Key Sectors. The U.S. government should identify and prioritize the distribution of IP in sectors where the U.S.-China industrial gap is widest and presents critical national security concerns (e.g., shipbuilding, rare earth processing, semiconductors, telecommunications equipment). The U.S. government should gather American producers of finished goods in these sectors, identify firms who would materially benefit from enhanced process capabilities as determined by the ability to scale production, reduce costs, or reduce production timelines, and distribute non-exclusive license to these firms. Because the firms compete on the finished goods, non-exclusive process licenses would not impact intra-sector competition but instead strengthen the herd. The U.S. government should also impose conditions these licenses to maximize return for the American people, such as dictating certain production timelines or cost ceilings, and revoke the licenses of those who fail to meet these conditions. This was the route that the U.S. government primarily utilized to quickly distribute German chemical and pharmaceutical IP during World War I.

-

Use Exclusive License to Reward Innovation and Incentivize IP Seizures. The U.S. government should also incentivize American firms to lean-in to Dark SBIR by offering exclusive licenses in certain circumstances. First, the U.S. government should hold contests among the above key sector firms and award exclusive licenses to winning firms that demonstrates truly significant accomplishments with seized Chinese process technologies (e.g., 75+% cost reduction or reduction in timeline). Second, the U.S. government should allocate exclusive licenses to firms that bring forward useful IP (either themselves or by sourcing third-party bounty hunters) that qualifies for seizure under TWEA reforms.

-

Utilize Public Domain Distribution for Non-Critical IP: The U.S. government may find itself processing a significant amount of processing IP that is subject to seizure under TWEA reforms but is not tied to use in critical national security sectors. In this case, the U.S. government should place the IP in the public domain. This was the approach that the U.S. government took during World War II took put the massive number of seized German and Japanese patents and copyrights to use. It is also the easiest approach from an administrative perspective.

20th Century Precedent

While such a proposal may sound unusual to our modern ears, Dark SBIR is not a novel concept. The United States successfully wielded TWEA authorities against Germany, Japan, and other Axis and Triple Alliance powers, though the most relevant use case is America’s first use of TWEA against German companies during World War I.13

At the outbreak of the Great War, America was almost entirely reliant on Germany for key chemicals, pharmaceutical inputs, and medical products. This reliance was not unique; the United States, the United Kingdom, and France purchased nearly all their intermediate and finished pharmaceutical products, inputs, and related chemicals from German companies via German-owned import firms.

As with China today, Germany’s dominance in industrial inputs and finished products was downstream from its dominance of process technologies. Decades before the war, Otto von Bismarck, Germany’s first Chancellor, initiated a whole-of-government effort to capture global industrial markets, including the chemical market.14 After unifying Germany, Bismarck sought to build out the fledgling nation’s manufacturing capacity, and began by carefully studying the industrial development of Germany’s chief rival, Great Britain. Bismarck and his advisors quickly derived and applied lessons. They reformed Germany’s education system to cultivate a generation of technical workers. They shielded Germany’s firms from foreign competition by erecting tariffs and other trade barriers. They designed a patent system that incentivized aggressive innovation and favored domestic firms. They provided tax benefits and promoted corporate consolidation. German firms took full advantage of the nation’s favorable environment and rapidly produced novel scientific and organizational advancements.

With the home front shored up, German firms looked abroad. They launched a coordinated effort to capture overseas markets with shrewd contractual language and targeted exploits of foreign corporate and IP laws. After German firms established a foothold, the German government collaborated with German trade groups to dump products and stifle competition. Specifically, German pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturers took advantage of the lack of a market introduction requirement in U.S. patent law—in the United States, a patent applicant or holder does not need to sell or oblige itself to sell the patented item in order to receive or maintain U.S. government IP protections. German firms therefore mass-filed process and technology patent applications for items that they had no intention of ever providing to U.S. consumers but could block U.S. firms from producing. In fact, one United States federal judge observed during litigation related to the seizure of German IP that German firms engaged in patent filing practices that were explicitly designed to discourage U.S. innovation. The judge highlighted that “any one who attempted to repeat the method for manufacturing a dyestuff protected by Salzmann & Krueger in the German patent No. 12,096 would be pretty certain to kill himself during the operation.”15

By the beginning of the war, 70 percent of all American patents for pharmaceutical synthetic compounds belong to German companies, and they were filed to prevent American inventors from reducing Germany’s market dominance. This effort was successful. While some U.S. firms had begun to hire scientists in an attempt to compete with German counterparts, they were unable to avoid the German patent wall. Further, German producers and importers would not sell them intermediary chemical inputs that could be used to design products that weren’t already patented. German pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturers had constructed dense corporate webs to manage the market access of their would-be U.S. competitors. For instance, Bayer, Merck, and Heyden each built and managed production plants in America and required that importing houses (typically owned by Americans) sign exclusive distribution contracts that barred the American importers from selling the products of non-German suppliers without permission from the German firm. By 1914, three of the largest six German pharmaceutical and chemical firms maintained their own importing agencies, and the other three worked through exclusive contracts with American-owned firms.

As a result, the United States, which was by many measures the world’s predominant industrial power, found itself with virtually no ability to manufacture finished pharmaceuticals or pharmaceutical inputs, including crucial drugs such as aspirin and Salvarsan (an anti-syphilitic second to none in importance because an estimated 1 in 5 American men were syphilitic during World War 1). Americans were aware of this vulnerability. A post-war U.S. government study concluded that the pre-war American pharmaceutical industry “consisted of little more than a series of rather small assembling plants [and] hardly any of the necessary intermediates [were] made here, and the manufacture of dyes was almost entirely confined to working upon intermediates imported from Germany.”16 A chemistry scholar reported that he was not aware of the United States producing even one organic chemical in the years before World War 1.17

The European blockade on Germany almost completely cut off German exports, exacerbating America’s reliance on German chemicals and pharmaceuticals. However, Americans could not step up to fill the gap because German firms had strategically utilized American IP law and drafted supplier and customer contracts to prevent new market entrants. America faced mass shortages of drugs and medical supplies. To make matters worse, Americans knew that paying high prices for the few products that made it through the blockade meant funding Germany’s war effort. What was to be done?

The medical community led the way. The American Medical Association (AMA) launched a nationwide lobbying campaign to pressure Congress to seize German patents so that Americans could make their own medicine. Reports of Germany’s abusive patent tactics began to flood the offices of American political leaders. In one report, a physician wrote with alarm that “[o]ur experience with salvarsan during the last two years has been almost intolerable … under these patents, the German owners and their American representative have made millions.”18 Charles Mayo, co-founder of the Mayo Clinic and future President of the AMA, wrote to the U.S. Surgeon General urging him to lobby Congress to “act immediately to suspend or abrogate German patents controlling manufacture of drugs necessary for public health maintenance especially Salvarsan.”19

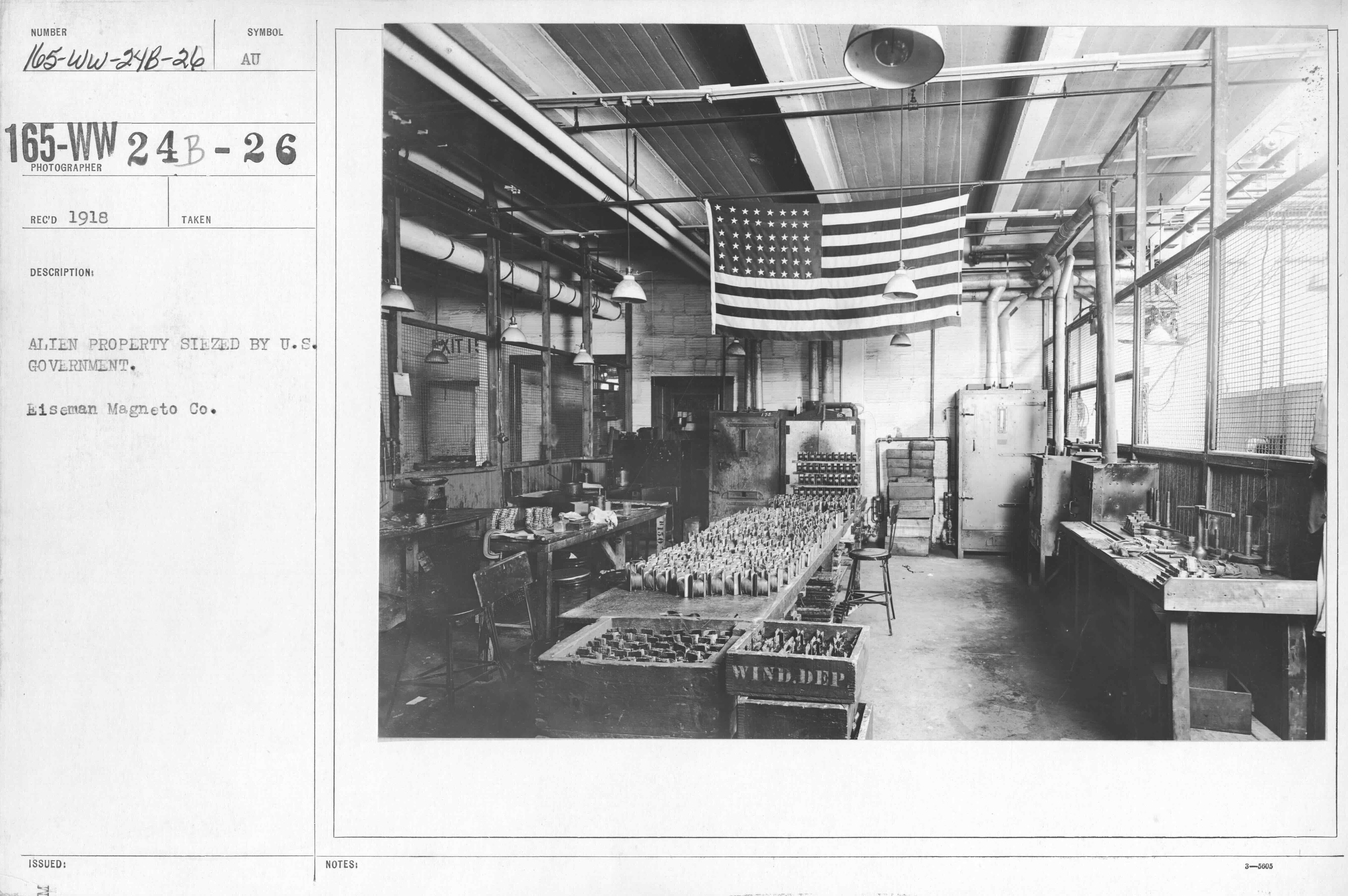

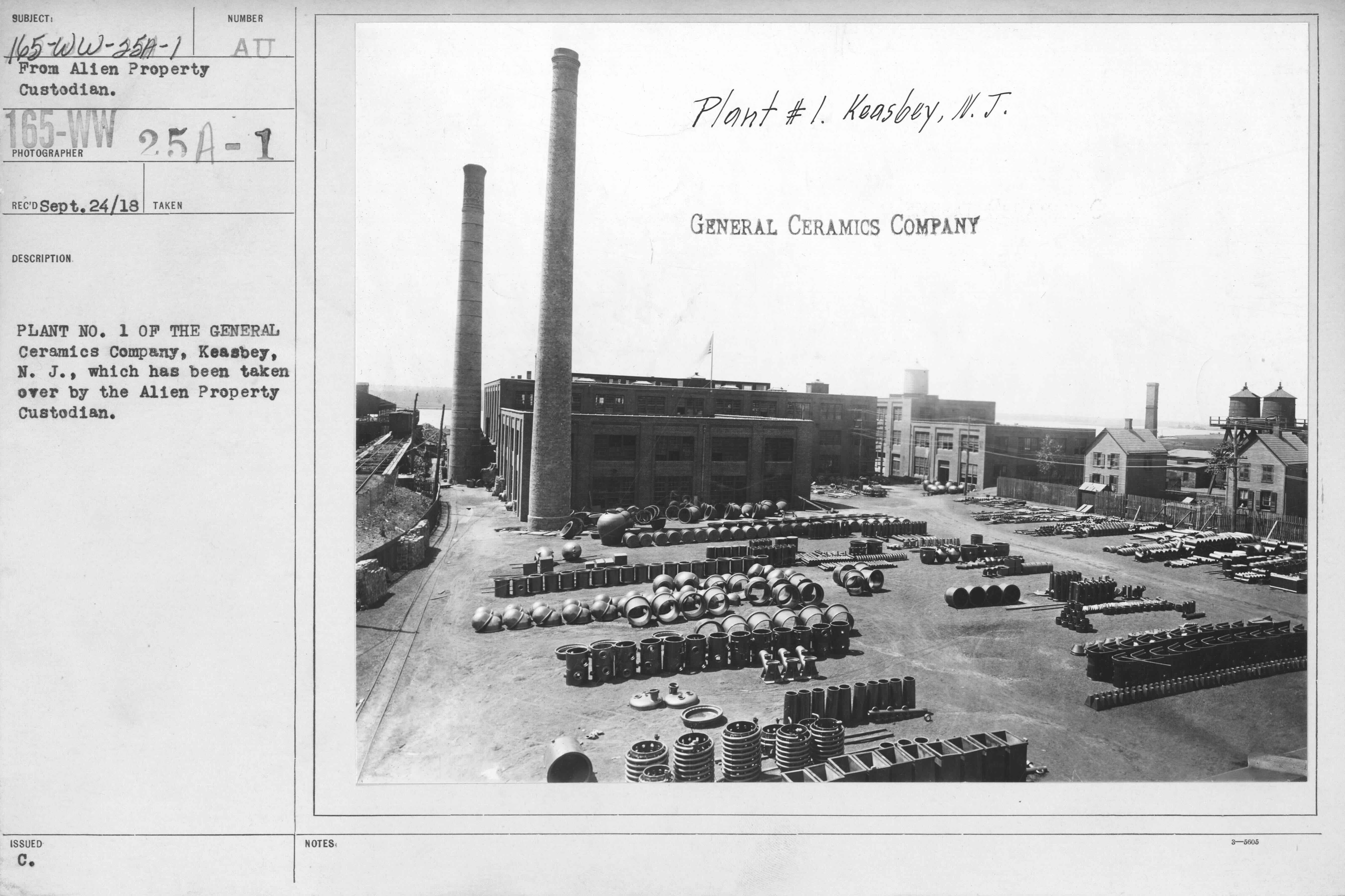

The pressure campaign succeeded. Congress passed a series of authorities that resulted in TWEA. Acting on these authorities, the U.S. government quickly commandeered German plants, distribution centers, assets, finances, and IP for pharmaceutical drugs (including Salvarsan and Novocain), stainless steels, synthetic ammonia, methanol, and the upstream inputs and equipment needed to produce and process these items. German IP was then publicized or licensed to over 100 American firms. The seized plants (primarily based on the east coast of the United States) were also distributed, and helped launch the then-fledgling American pharmaceutical sector (both Dow Chemical and the DuPont company expanded into organic chemicals during the war, and the seizure of leading German facilities, based in New Jersey, no doubt contributed to the clustering of today’s American pharmaceutical firms in the mid-Atlantic).

The United States reached again for TWEA authorities during World War II, seizing nearly 500 million in property, 46,000 patents and inventions, 500,000 copyrights, and Axis interests in 414 companies. Leo T. Crowley, the official leading the seizure and distribution of Axis IP and assets, described his mission as one that would “destroy the military might” of the Axis powers and “create the material well-being which in post war years will form a strong bulwark of the free world for which we now struggle.”20 Let us do so again.

Conclusion

Our adversaries have not waited for a formal declaration of war to undermine our national security, degrade our industrial capacity, and cut off the material needed to power our economy.

Congress must reform TWEA to authorize the seizure and distribution of crucial technological processes developed on the back of decades of stolen American ingenuity. Again, the United States will use these authorities during war. But Congress should not allow our adversaries to choose the hour of decision.

We must fight back, and we can suffer no more wasted time.

–

-

Joe Deaux, Why Rare Earths Are China’s Trump Card in Trade War With US, Bloomberg (October 9, 2025), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-09/how-china-s-rare-earths-dominance-is-leverage-in-trump-s-trade-war; International Energy Agency, Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024 (May 2024), https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ee01701d-1d5c-4ba8-9df6-abeeac9de99a/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2024.pdf. ↩

-

Daniel Burke, PRC Consolidates Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Dominance, Jamestown Foundation (September 19, 2025), https://jamestown.org/program/prc-consolidates-pharmaceutical-supply-chain-dominance/; Marta E. Wosińska & Yihan Shi, US drug supply chain exposure to China Myths, omissions, and related insights, Brookings Institution (July 28, 2025), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-drug-supply-chain-exposure-to-china/. ↩

-

Office of the United States Trade Representative, Four-Year Review of Actions Taken in The Section 301 Investigation: China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation (2024). ↩

-

Garrett Murch & Scott Maier, Medical Manufacturing: A Critical Supply Chain at Risk, 9:4 American Affairs (2025), https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2025/02/medical-manufacturing-a-critical-supply-chain-at-risk/#notes. ↩

-

See Ryan McMorrow & Demetri Sevastopulo, China unveils sweeping rare-earth export controls to protect ‘national security’, Financial Times (Oct. 8, 2025), https://www.ft.com/content/c4b2c5d9-c82f-401e-b763-bc9581019cb7. ↩

-

Zhong Caiwen [钟才文], Comprehensively Understanding and Grasping the Certainty of High-Quality Development of China's Economy (Special Report on China's Economy under the Guidance of Xi Jinping's Economic Thought) [全面认识把握中国经济高质量发展的确定性 (习近平经济思想指引下的中国经济专论)], People’s Daily (October 4, 2025), http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/1004/c1003-40576574.html. ↩

-

Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, X, October 10, 2025, 12:35pm ET, https://x.com/ChinaSelect/status/1976688130464821639. ↩

-

Donald Nelson, Salvage for Technology - Ensuring critical minerals in wartime, Defense Analyses Research Corporation, https://defenseanalyses.org/work/salvage-for-technology/. ↩

-

Joel B. Predd, et. al, Thinking Through Protracted War with China, RAND Corporation (February 26, 2025), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1475-1.html; Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, Select Committee on the CCP Holds Defense Industrial Base Simulation (Nov. 22, 2024), https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/media/press-releases/media-package-select-committee-ccp-holds-defense-industrial-base-simulation. ↩

-

See, e.g., Executive Order 14352, Saving TikTok While Protecting National Security, 90 Fed. Reg. 47219 (September 25, 2025), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/09/30/2025-19139/saving-tiktok-while-protecting-national-security. ↩

-

For data on Chinese engineers, see Jonathon P. Sine, Litigation Nation, Engineering Empire (August 27, 2025), https://substack.com/@jonathonpsine/p-169678747. ↩

-

See Nick Ingram, Michael Goldberg, & Heather Hollingsworth, North Korean charged in cyberattacks on US hospitals, NASA and military bases, Reuters (July 25, 2024), https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-hacker-military-intelligence-hospitals-b3153dc0ad16652a80a9263856d63444; Lily Hay Newman, North Korea Targets—and Dupes—a Slew of Cybersecurity Pros, Wired (January 26, 2021), https://www.wired.com/story/north-korea-hackers-target-cybersecurity-researchers/; David E. Sanger & Nicole Perlroth, U.S. Said to Find North Korea Ordered Cyberattack on Sony, The New York Times (January 8, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/18/world/asia/us-links-north-korea-to-sony-hacking.html?\_r=0. ↩

-

For this section, see Kathryn Steen, The American Synthetic Organic Chemicals Industry War And Politics, 1910-1930 (U.N.C. Press, 2014). See also Nicholas Mulder, The Trading with the Enemy Acts in the age of expropriation, 1914-49, 15 Journal of Global History 81-88 (2020); Benjamin A. Coates, The Secret Life of Statutes: A Century of the Trading with the Enemy Act, 1 Modern American History, 151-157 (2018); Arthur Daemmrich, Pharmaceutical Manufacturing in America: A Brief History, 59 History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals, 63 (2017); Dale Cooper, The Licensing of German Drug Patents Confiscated During World War I: Federal and Private Efforts to Maintain Control, Promote Production, and Protect Public Health, 54 History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals, 3 (2012); Declan O’Reilly, Vesting GAF Corporation: The Roosevelt Administration’s Decision to Americanise I.G. Farben’s American Affiliates in World War II, 22 History and Technology, 153-158 (2006); Dale Cooper, The Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 and Synthetic Drugs: Relieving Scarcity, Controlling Prices, and Establishing Pre-Marketing Licensing Controls, 47 History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals, 48 (2005). ↩

-

Luigi Palombi, Gene Cartels: Biotech Patents in the Age of Free Trade 44-46 (Edward Elgar Pub., 2009). ↩

-

U.S. v. The Chemical Foundation, 294 F. 300, 318 (1924). ↩

-

Alien Property Custodian Report, Government Printing Office (Washington, D.C., 1919), 7, 499-504. ↩

-

William Haynes, The World War I Period: 1912-1922, in American Chemical Industry vol. 3 (New York, 1945), 311. ↩

-

Letter to the Editor: Abolition of the Patents on Salvarsan, 68 Journal of the American Medical Association, 1153, 1203-1204 (Apr. 21, 1917). ↩

-

Letter from Charles H. Mayo to Surgeon General Rupert Blue (April 14, 1917), in 90 Records of the Public Health Service, Central File 1897-1923 3655 (National Archives, College Park, MD, April-Aug. 1917. ↩

-

Michael J. White, US Alien Property Custodian patent documents: A legacy prior art collection from World War II – Part 2. Statistics, 30 World Patent Information, 34 (2008); Michael J. White, US Alien Property Custodian patent documents: A legacy prior art collection from World War II – Part 1. History, 29 World Patent Information, 339-342 (2007). ↩