This memo argues for the territorialization of Cuba by the United States. Substantial geostrategic and economic benefits are identified. Pathways to territorialization are described. It concludes by outlining potential legal frameworks and existing models of territorialization.

Cuba as a Case Study in the Illusion of Grand Strategy

The U.S. has been unable to pursue a coherent grand strategy since the close of the Cold War.1 Absent grand strategy, foreign policy tends to be driven by a combination of historical contingency, elected officials responding to public opinion, and interest groups—including foreign lobbies.2 The last decade of Cuban–American relations are a case-in-point. After the reestablishment of diplomatic relations by the Obama administration in July 2015, the outgoing Obama administration allowed for expanded remittances, people-to-people travel, and rescinded Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terror.3 The restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba can be explained as an attempt to reflect public opinion towards Cuba, which has long favored the end of the embargo.4 Balanced against public opinion is the power of anti-Communist Cuban-American interest groups within the Republican Party.

The shifting state sponsor of terror designation provides a simple illustration of these dynamics. The designation, made by the Secretary of State in consultation with the President and the National Security Council, triggers a cascade of sanctions, reduced diplomatic engagement by other countries, and close monitoring by the U.S. intelligence community. In 2021, the outgoing Trump administration reinstated Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism. On January 14th, 2025, the outgoing Biden administration rescinded Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism.5 A week later, the incoming Trump administration reversed the rescission and redesignated Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism.6 The question of whether a state is a sponsor of terror would, on the surface, appear to be one that could be objectively settled via reference to recent acts of terrorism. For Cuba however, the designation reflected the seesawing fortunes of the Democratic party, which has deferred to majoritarian prerogatives in foreign policy, and the Republican party, which has deferred to concentrated interests embodied in Cuban exiles and their descendants. Absent a coherent grand strategy for the Western hemisphere, American foreign policy towards Cuba will remain forever subject to policy inconsistency and reversals.

This paper outlines a grand strategy towards Cuba based on realist principles. It takes the position that Cuba has not been successfully self-governing for over a century. Absent self-governance capacity, the welfare of both the existing Cuban and the American populations would improve from U.S. territorialization of Cuba.

The next section discusses the geostrategic benefits of territorialization. The section thereafter considers strategic commodities found in Cuba. Next, trade opportunities from a territorialized Cuba are reviewed. Then, the section titled paths to territorialization briefly discusses three options for policymakers. Finally, options for the legal status of Cuban natives in a hypothetical territorialized Cuba are summarized. I conclude this memo with “Towards a Grand Strategy for the Western Hemisphere” by elucidating how the proposed American foreign policy towards Cuba fits into a broader grand strategy. A historical review in the Appendix follows.

Geostrategic Benefits

There are two main geostrategic benefits from territorializing Cuba. First, Cuba is major SIGINT and missile vulnerability for the mainland United States because it is located only 90 miles from U.S. shores. Second, Cuba’s location in the center of the Caribbean makes it convenient for any renewed commitment to intervention in the Western hemisphere.

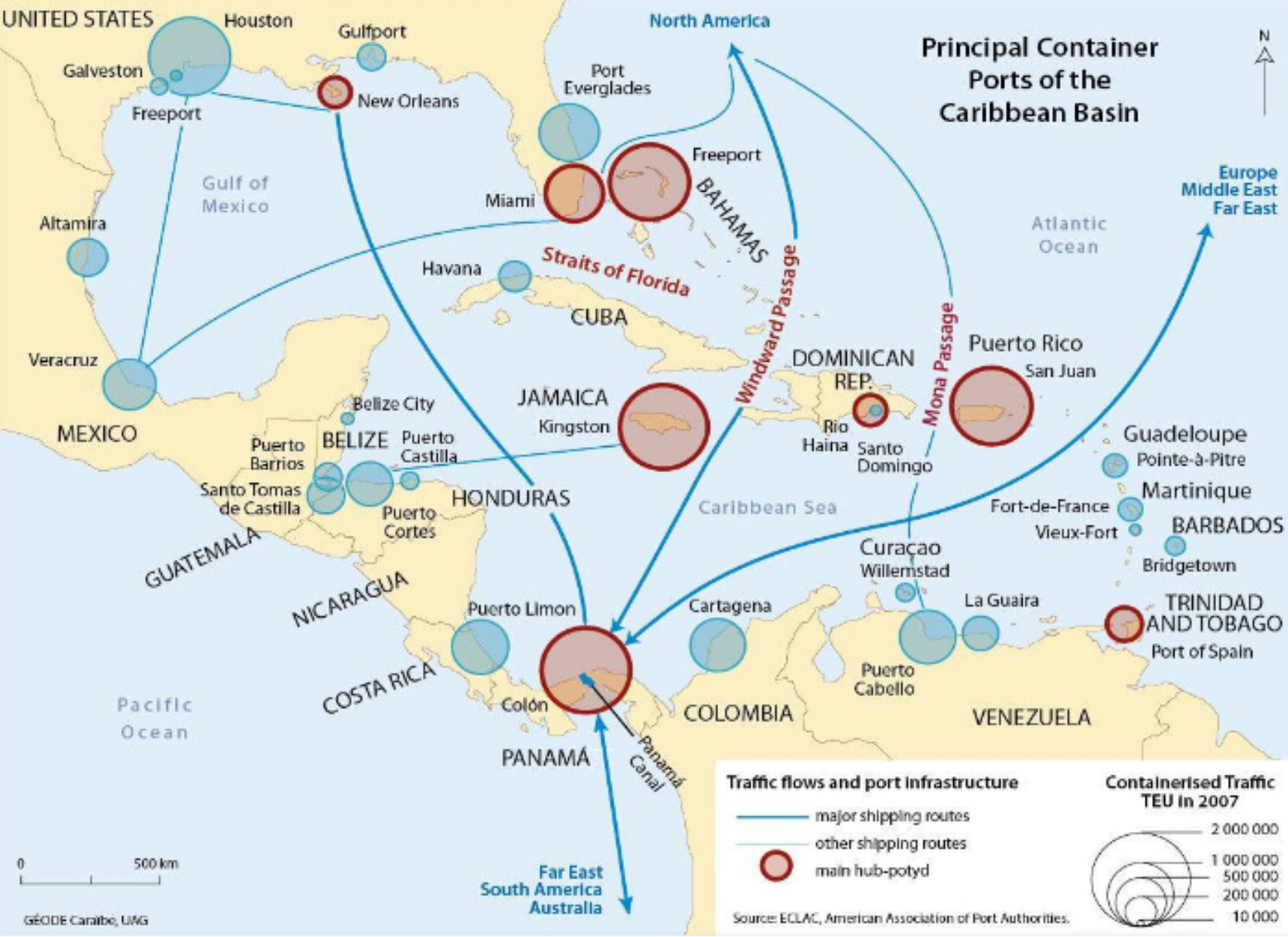

FIGURE 1. Principal Container Ports of the Caribbean Basin. Sourced from “The Cuba Effect: What Normalized United States–Cuba Relations Means for Economies and Freight Flows in the Gulf of Mexico” (Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2016)

American naval officer and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan presciently observed Cuba’s geostrategic value as early as 1897 (at the time still under Spanish control):7

It is in this respect that the preeminent intrinsic advantages of Cuba, or rather of Spain in Cuba, are to be seen; and also, but in much less degree, those of Great Britain in Jamaica. Cuba, though narrow throughout, is over six hundred miles long, from Cape San Antonio to Cape Maisi . . . In area it is half as large again as Ireland, but, owing to its peculiar form, is much more than twice as long. Marine distances, therefore, are drawn out to an extreme degree. Its many natural harbors concentrate themselves, to a military examination, into three principal groups, whose representatives are, in the west, Havana; in the east, Santiago; while near midway of the southern shore lies Cienfuegos. The shortest water distance separating any two of these is 335 miles, from Santiago to Cienfuegos. To get from Cienfuegos to Havana 450 miles of water must be traversed and the western point of the island doubled; yet the two ports are distant by land only a little more than a hundred miles of fairly easy country. Regarded, therefore, as a base of naval operations, as a source of supplies to a fleet, Cuba presents a condition wholly unique among the islands of the Caribbean and of the Gulf of Mexico; to both which it, and it alone of all the archipelago, belongs . . . The extent of the coast-line, the numerous harbors, and the many directions from which approach can be made, minimize the dangers of total blockade, to which all islands are subject. Such conditions are in themselves advantageous, but they are especially so to a navy inferior to its adversary, for they convey the power—subject, of course, to conditions of skill—of shifting operations from side to side, and finding refuge and supplies in either direction.

As this analysis suggests, Cuba’s unique geographic location, especially its size and proximity to the U.S., ensures that it will play an important role in any assertion of American power in the Western hemisphere. I divide geostrategic considerations into two parts. First, those relating to U.S. adversaries in the Eastern hemisphere and second to a mix of allies and adversaries in the Western hemisphere. Generally, Cuba’s relationship with the U.S. is analogous to Taiwan’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China—a nearby launching pad for operations by the U.S.’s adversaries and a major SIGINT weakness. On the other hand, the incorporation of Cuba as a U.S. territory offers economic and security opportunities with regards to the broader Western hemisphere.

Eliminating Eastern Hemisphere Threats

The primary benefit of territorialization is to completely eliminate the threat illustrated by the Cuban missile crisis. The possibility of decapitation strikes via intermediate range atomic weapons is remote, but nonzero. The probability that great powers in the Eastern hemisphere, i.e. the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Russia, have used and will continue to use Cuba for both SIGINT and conventional operations is much larger.

The Cuba–Venezuela relationship is already deep, and the intervention of a third party (Russia or, more likely, the PRC) could raise the stakes significantly. Russian news agency TASS reported in 2018 that:

Russian authorities have made a decision (and Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro did not object) to deploy strategic aircraft to one of Venezuela’s islands in the Caribbean Sea, which has a naval base and a military airfield. Ten years ago, Russian experts and Armed Forces commanders had already visited the island of La Orchila, located 200 kilometers northeast of Caracas. Venezuelan laws prohibit the setup of military bases in the country, but a temporary deployment of warplanes is possible.8

When Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu visited Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela in 2015, the trip was specifically made in response to US support of Euromaidan, with the editors of Pravda quoting him as saying that:9

If such Russian vessels are deployed somewhere near the territory of Cuba, they will be able to attack the United States. This is our response to the deployment of U.S. military objects near the Russian border…The United States is quite vulnerable. One may eventually have to create missile defense from the side of Florida, rather than Alaska. All these issues arise and require huge financial resources. I think it will convince the United States of the shortsightedness of this kind of policy.

Additional agreements between Russia and Venezuela on counter-espionage and intelligence sharing were signed in 2024. A friendly Cuba would greatly reduce the potential danger from any future Venezuela-Russia agreements to the U.S. mainland.

A December 2024 report from CSIS, based on satellite imagery and OSINT analysis, suggests that the PRC has developed considerable SIGINT capabilities in Cuba.10 The four sites in question are located in Bejucal, Wajay, Calabazar and El Salao. The former three are all in proximity to municipal boroughs around Havana. The sites are within antenna range of Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Some of these sites even have solar farm installations, possibly as backup power given the unreliability of the Cuban grid. There is evidence of recent military visits between Chinese and Cuban officers. On April 15, 2024, General He Weidong, a member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission (CMC), met with General Víctor Rojo Ramos, a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba and chief of the Political Directorate of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.11

Cuba was a significant theme in SOUTHCOM’s 2014 posture statement to the House Armed Services Committee. It follows that territorializing Cuba would relieve much of the U.S.’s defense burden in the Caribbean. Cuba’s cooperation with the PRC and Russia as well its potential for integration into the BRICS bloc were emphasized:12

Both the PRC and Russia are taking advantage of the existing conditions within Cuba to deepen cooperation across all elements of national power, with President Díaz-Canel commenting during last summer’s BRICS Summit in South Africa that Cuban–Chinese relations were at an all-time high. On November 6th of 2023, President Xi Jinping met with Cuban Vice Prime Minister Manuel Marrero Cruz in Beijing, affirming China’s willingness to support Cuba’s defense of national sovereignty.

It is remarkable that, given the widespread acknowledgement that Cuba poses a substantial economic and security vulnerability, policymakers have simply been unwilling to publicly entertain either direct military intervention or incorporation. Territorializing Cuba would completely and directly eliminate potential threats arising from conventional forces.13 This possibility that our adversaries might station conventional forces in Cuba is no longer remote. Cuba’s partnership in the PRC-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and close diplomatic ties with the PRC leave the Cuban state vulnerable to pressure by the PRC to station conventional Chinese forces should the contingency arise.14 Aid from the BRI is conditional and it has become common for the PRC or PRC-aligned companies to seize infrastructure as collateral when a debtor nation fails to make payments. Cuba has consistently failed to meet contractual obligations under the BRI because of its domestic economic dysfunction. Import volumes of Chinese goods into Cuba were declining between 2017 and 2022. The Cuban sugar industry’s output has plummeted, and the original export agreement with the PRC to deliver 400,000 tons of sugar annually has been scrapped. Cuba does not have the resources to pay off its debts to Chinese companies such as Huawei and Yutong (for telecom and electric buses, respectively). It remains to be seen whether the PRC will reduce the footprint of BRI in Cuba or take advantage of Cuba’s failure to make payments to obtain a more formal military foothold in the Caribbean.15

Western Hemisphere Opportunities

Surprisingly, the U.S. already cooperates with Cuba in many ways. Reviewing both the existing security-adjacent joint ventures and missed opportunities for cooperation illustrates why a territorialized Cuba would provide substantial security benefits in the Western hemisphere.

First, there has been a non-trivial degree of cooperation between the US Coast Guard and the Cuban Border Guard since the 1990s owing to a common interest in counteracting narcotics and human trafficking.16 The State Department Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs remarked in its 2016 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report that:17

With respect to international cooperation, the Cuban government reports 36 bilateral agreements for counterdrug cooperation and 27 for policing cooperation. The U.S. Embassy maintains a U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) liaison to coordinate with Cuban law enforcement. USCG and Cuban authorities share tactical information related to vessels transiting Cuban territorial waters suspected of trafficking and coordinate responses. Cuba also shares real-time tactical information with the Bahamas, Mexico, and Jamaica. Bilateral cooperation in 2015 led to multiple interdictions; Cuban cooperation with USCG led to the August arrest of three Bahamian citizens involved in drug trafficking activities, and the seizure of the “go-fast” boat used for those activities.

The State Department reported that on July 22, 2016 working-level representatives from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), U.S. Coast Guard (USGC), Immigration and Customs Enforcement-Homeland Security Investigations (ICE/HSI), and the Department of State signed a Counternarcotics Arrangement, “which will facilitate further cooperation and information sharing between Cuba and the United States in our common effort against illegal narcotics trafficking.”18 Just four days prior to the Trump administration, it was announced on January 16, 2017 that the United States and Cuba “will continue the Law Enforcement Dialogue process, which includes technical exchanges on specific law enforcement issues of mutual concern such as counternarcotics, money laundering, fraud and human smuggling, and counterterrorism.”19

Some cooperation also exists between the Cuban brigadier general at Guantanamo and the US Navy captain. “Coincident firefighting maneuvers” have been conducted by both sides, involving helicopters carrying water bags. Each side is reportedly prepared to provide medical support to the other in emergencies, for example, by evacuating burn victims to the closest hospital. Havana also had no objection to the stationing of Al-Qaeda suspects, and agreed to return any escapees back to the existing Guantanamo Bay base.20

Several thousand maritime interdictions of illegal Cuban migrants are made every year. 2014 was a peak year, with 25,000 apprehensions.21 This was due to the so-called “wet feet, dry feet policy,” an interpretation of the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 under which migrants caught at land as opposed to at sea would not be returned back to Cuba. This policy was rescinded in 2017, but similar “demand-pull” factors include the Cuban Family Reunification Parole program, under which 500,000 known Cuban migrants entered the United States from 2021 to 2024. Although this program was also recently halted, policymakers are likely to continue such policies for as long as embargoes and travel restrictions are pursued under the justification of human rights.

Outside of narcotics, Guantanamo Bay fire management, and immigration enforcement, security cooperation between Cuba and the United States has been limited. The sharpest difference between Cuba and peer nations in the Caribbean and Latin America, e.g. Colombia, Argentina, Chile, and Mexico concerns extradition. Cuba and the U.S. maintain no extradition agreements or policy infrastructure. A revived extradition agreement or case-by-case prisoner transfers would ensure that dangerous criminals can no longer evade justice by hiding in the other country. U.S. fugitives who have committed murder, armed robbery, or terrorism would face trial in American courts, improving justice and deterring others from seeing Cuba as a safe haven. Likewise, individuals who commit violent crimes in Cuba and flee to Florida could be returned, reducing bilateral frictions. Moreover, restoring the counterterrorism information pipeline could be literally life-saving—as seen in 2018 when Cuba detained an American extremist due to an FBI alert.22 If that channel is institutionalized, any time a terror suspect or internationally-wanted criminal passes through Cuban territory (or U.S. territory), each side could immediately notify the other and coordinate an arrest. Such real-time intelligence exchange (akin to what the U.S. has with European allies for counterterrorism) would close off a potential loophole in U.S. homeland security. It is worth noting that after the U.S. and Cuba resumed security talks in 2023, the State Department acknowledged Cuba’s improved counterterrorism cooperation and removed Cuba from its list of uncooperative countries—a sign of the tangible benefit to U.S. security when Cuba is engaged.23 Further engagement could only strengthen the U.S.’s hand against terrorist travel or financing in the region.

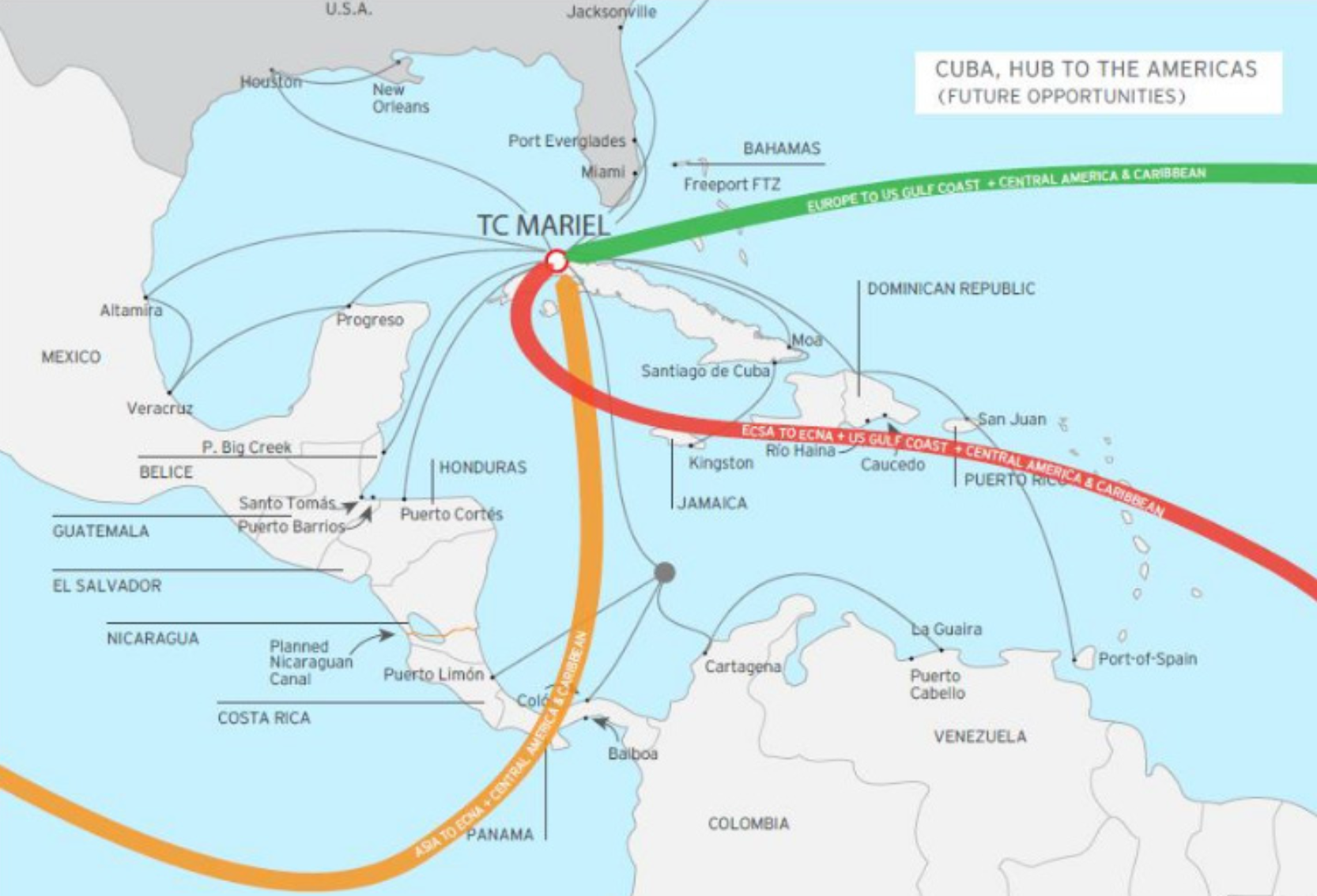

Finally, access to Cuban ports would enable the U.S. Navy to more easily project power throughout the Western hemisphere. Consider the Port of Mariel, which opened in 2014 with an estimated capacity of 800,000 TEU. The Port of Mariel, positioned right in the center of the Gulf, provides direct access to the Straits of Florida and the Windward Passage, as well as proximity to the transshipment hub ports of Freeport (Bahamas), Kingston (Jamaica), Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), San Juan (Puerto Rico), and Port of Spain (Trinidad and Tobago).

FIGURE 2. Port of Mariel’s strategic location. Sourced from ZED Mariel

Overall, there are four clear Western hemisphere-specific geostrategic benefits from closer cooperation with Cuba. First, deeper cooperation would allow for a more complete interdiction of drugs and cessation of human trafficking across the straits of Florida and Caribbean sea. Second, greater cooperation would enable the current administration to more easily control illegal immigration. Third, a territorialized Cuba would yield crime control benefits and patch a legal backdoor commonly used by local criminals, cartel gangs, and terrorists. Fourth, the U.S. would be more easily conduct operations in Haiti, Nicaragua, Colombia, and especially Venezuela, where tensions have risen considerably. Territorialization would maximize the benefits arising from closer cooperation. For instance, a territorialized Cuba could potentially see the remigration of 3–4 million Cubans currently in the United States. Economic development arising from territorialization, discussed in detail below, would be expected to further reduce Cuban emigration to the U.S. and resolve conflicts and tensions arising from the “wet feet, dry feet policy” and successor policies. Similarly, access to Cuban ports would enable the U.S. Navy to cheaply project power throughout the Caribbean and South America.

Strategic Commodities

Cuba’s inability to exploit its own resource base has left it with a large, undeveloped stock of minerals and other strategic commodities. Mahan remarked in 1897 that Cuba was:

[N]ot so much an island as a continent, susceptible, under proper development, of great resources — of self-sufficingness . . . unique in its size, which should render it largely self-supporting, either by its own products, or by the accumulation of foreign necessaries which naturally obtains in a large and prosperous maritime community; and it is unique in that such supplies can be conveyed from one point to the other, according to the needs of a fleet, by interior lines, not exposed to risks of maritime capture.

The United States maintains a list of critical minerals compiled by the US Geological Survey at the behest of the Secretary of the Interior. Sections 7002(a) and (c) of the Energy Act of 2020 define a “critical mineral” as any mineral, element, substance, or material designated as critical by the Secretary of the Interior, acting through the Director of the USGS using three criteria, which are:

(i) essential to the economic or national security of the United States; (ii) the supply chain of which is vulnerable to disruptions (including restrictions associated with foreign political risk, abrupt demand growth, military conflict, violent unrest, anti-competitive or protectionist behaviors, and other risks throughout the supply chain); and (iii) serve an essential function in the manufacturing of a product (including energy technology-, defense-, currency-, agriculture-, consumer electronics-, and healthcare-related applications), the absence of which would have significant consequences for the economic or national security of the United States.

This memo takes the position that Cuban territorialization would significantly contribute to alleviating the scarcity of critical minerals in the U.S.

Consumption demand for cobalt has been steadily rising since the early 2010s, since it as an essential rare earth mineral for the production of lithium-ion batteries.24 The U.S. remains largely dependent on cobalt imports from the Congo, the resource base of which is overwhelmingly controlled by Chinese firms. Cuba’s unexploited cobalt reserves are estimated at ~500,000 metric tons.25 Cuba also contains significant unexploited reserves of nickel, zinc, and petroleum. Nonetheless, in 2019, the country was estimated to rank fifth among the world’s leading producers of cobalt, ninth among the world’s leading producers of nickel, and eighth among the world’s leading producers of zeolites.

The stringent nature of U.S. export controls means that any product which is “contaminated” by Cuban cobalt as an intermediary good during production, is immediately subject to embargo. For instance, this has prevented Tesla from importing goods from Panasonic sourced with Cuban inputs:26

Panasonic has suspended ties with a Canadian supplier amid concerns that Cuban cobalt, a target of US sanctions, was used in batteries it supplied for Tesla’s electric vehicles. The Japanese battery supplier said on Friday it did not know how much Cuban cobalt was ultimately used in the lithium ion batteries it supplied to the US market for Tesla “due to commingling of sources by its suppliers in several phases of manufacturing processes”. The company declined to identify its Canadian supplier but a person with knowledge of Panasonic’s supply chain identified the company as Sherritt International. The Canadian company produces cobalt at the Moa mine in Cuba through a joint venture with the Cuban state-owned General Nickel Company. Sherritt declined to comment. Panasonic said the suspension of ties was a precautionary measure following guidance from the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control over the scope of the US ban on Cuban-origin imports, which dates back to 1960. Tesla said it had been informed by Panasonic that a small portion of Model S and Model X batteries may contain trace amounts of cobalt from Sherritt. Only some vehicles produced after February 2018 are affected, and there is no impact on battery cells produced at its gigafactory in Nevada, including for its mass-market Model 3 cars.

As suggested above, the primary private firm contracting with the Cuban state to exploit rare earth minerals is the Canadian company Sherritt International, which has a 50:50 joint venture with the Cuban government known as Moa Nickel S.A. It processes mixed sulfides (nickel-cobalt) at Moa, Holguin Province, which are then shipped by ocean freight and refined in Alberta. The company’s concessions cover a total area of 12,322 hectares.27 Mining is nevertheless no more than 1% of total Cuban employment, at roughly 22,000 workers.28 There are also zinc deposits in Pinar del Rio. In 2017 Reuters reported:29

The $278 million Castellanos mine in western Pinar del Rio province is slated to annually produce 100,000 tons of zinc concentrate and 50,000 tons of lead concentrate, said the joint venture overseeing the project, Emincar, which brings together Swiss-based commodities giant Trafigura and Cuban state firm Geominera.

The state of cobalt and zinc deposits in Cuba illustrate two general findings of this report. First, Cuba’s precarious economic condition leaves them dependent on potentially hostile powers. Second, Canada’s cooperation with Cuba demonstrates that some mutually beneficial arrangements are at least possible. Although territorialization is a preferred outcome and would generate maximal economic benefits, reducing U.S. import controls would also generate additional economic activity for U.S. companies and the U.S.’s primary sector workforce.

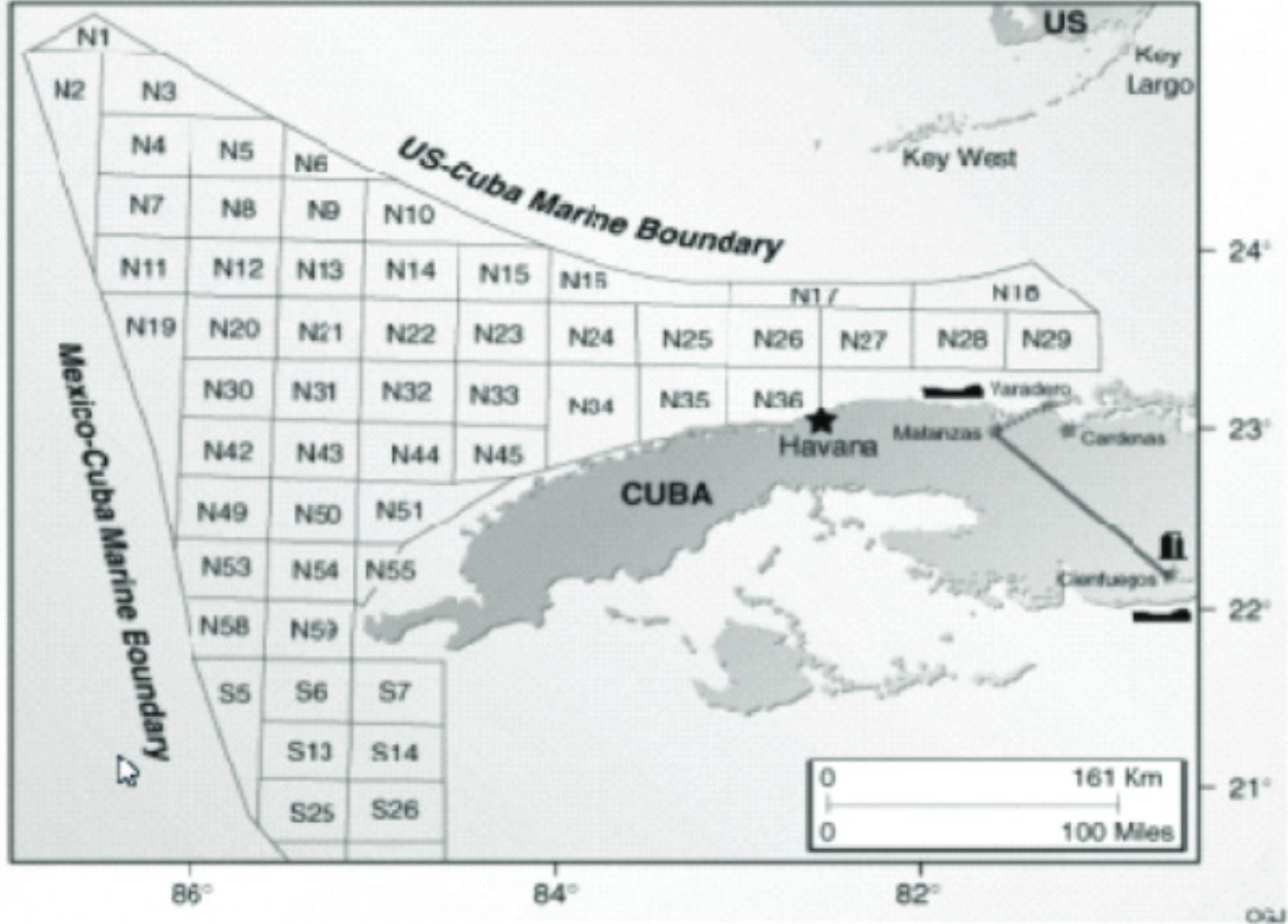

Cuba also has untapped offshore oil directly to its north that is variously estimated as ranging from 5 to 20 billion barrels.30 The island consumes about ~180,000 barrels a day. Cuba’s limited domestic extraction capacity ensures that it remains dependent on subsidized Venezuelan crude. There exists limited exploitation of land-based wells in the Mantanzas/Varadero region, but the government has neither the resources nor experience to exploit its potential deepwater reserves. The issue is logistical, but compounded by sanctions. As told by H. Michael Erisman, the major technological setbacks are that:

[F]irst, more than 80 percent of Cuba’s international waters are considered deep and ultra-deep, which means most oil wells will have to be drilled at more than 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) below the sea; one 2012 exploratory effort, for example, operated at 4,666 meters (15,308 feet). Second, the deposits are located under extremely hard rock which is very difficult to penetrate, quickly wearing down drilling bits, and are so dense that oil does not easily flow through it. These two factors combined make exploratory drilling a technologically daunting and very financially risky proposition – a dry hole can mean that investors will lose at least US$200 to US$250 million.

The United States has the human, organizational, and financial capital required to exploit the offshore oil reserves that Cuba lacks.

FIGURE 3. Potential offshore oil areas in Cuba. Sourced from H. Michael Erisman. Cuba as a Hemispheric Petropower: Prospects and Consequences. International Journal of Cuban Studies. 2019. Vol. 11(1):43-60. DOI: 10.13169/intejcubastud.11.1.0043

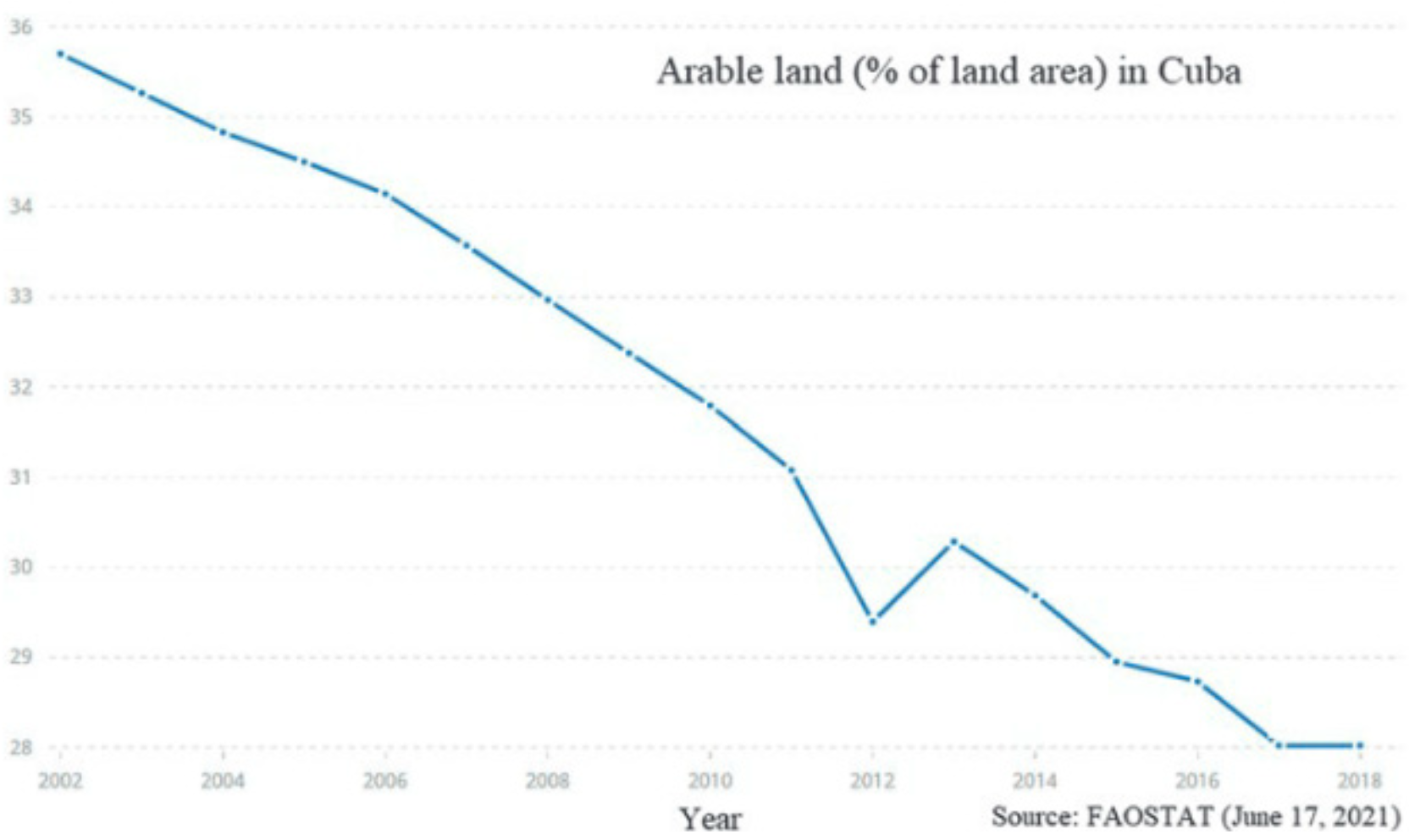

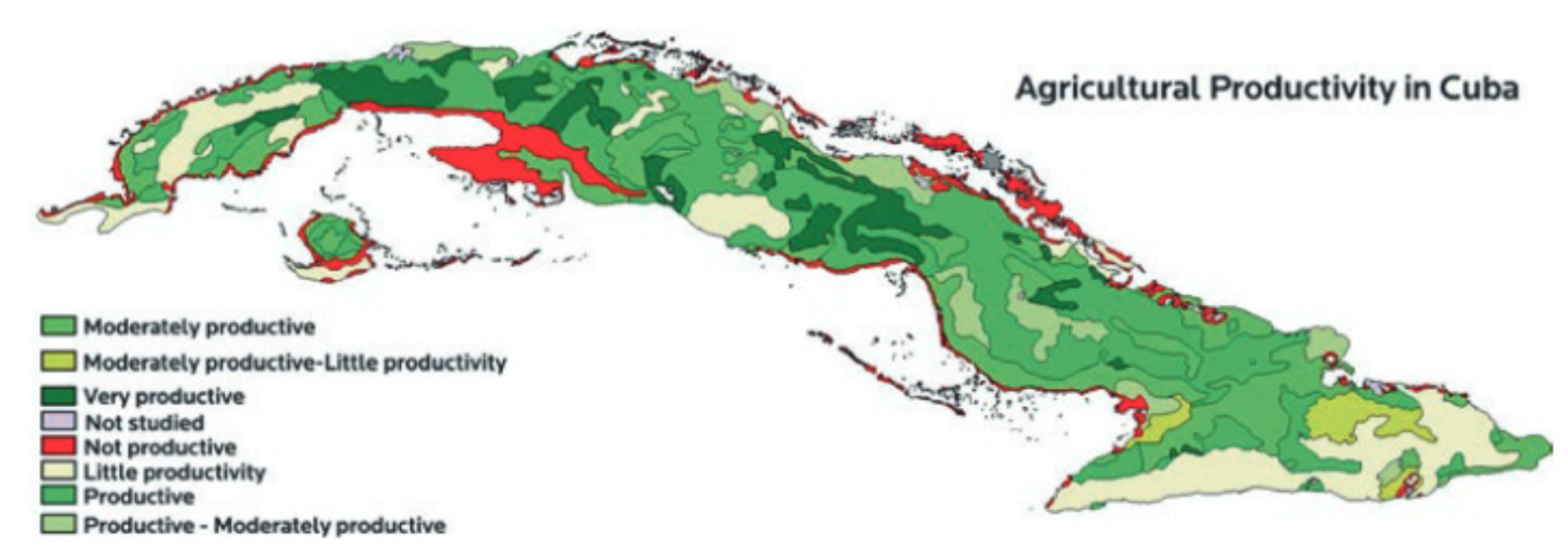

Geographic studies by Jennifer Gebelein have shown that the Cuban government’s land use policies are inefficient. Roughly half of Cuba’s existing arable land is uncultivated:31

Despite the successful transition in organic nutrients and pesticide management strategies during this period, in 2007, only about two million hectares of land were actively cultivated, in spite of the fact there were over four million hectares of fertile lands available. During the early years of the Special Period there was a national effort to stimulate planting food. However, stimulation did not last through the reanimation of the economy period; and from 1999 to 2007 cultivated land decreased by 17.5% overall. This is a significant change in land use and the reason behind it is that while Cubans may have access to the lands and the desire to farm them, they do not have the necessary resources to produce a crop yield. This decrease is not only in one area in Cuba, but exists in every province according to data analysed from 2002 to 2007.

FIGURE 4. Decline in arable land as percentage of land area in Cuba over time. Source: Gebelein, J., 2011. A Geographic Perspective of Cuban Landscapes. Springer, Dordrecht, Heidelberg.

FIGURE 5. Differential agricultural productivity of Cuban land mass. Source: Gebelein, J., 2011. A Geographic Perspective of Cuban Landscapes. Springer, Dordrecht, Heidelberg.

Trade Opportunities

During the 2015 thaw in relations, lobbying groups and the U.S. government produced a number of reports documenting the benefits of relaxing Cuban export controls. For example, a 2015 report by USITC was commissioned for the express purpose of estimating US export values to Cuba in the counterfactual event of no sanctions and no internal barriers to trade.32 The closest point of comparison is the Dominican Republic (DR), a country with comparable conditions, population, per-capita income and commodity profiles (sugar, cement, tobacco). Whereas the US accounts for 41% of the DR’s merchandise imports in 2014, only 3% of Cuba’s merchandise imports are from the U.S. According to USITC model projections:

The analysis estimates that if U.S. restrictions on U.S. exports to Cuba were lifted, U.S. exports to Cuba of the selected agricultural and manufactured products would increase to approximately $1.8 billion annually. U.S. exports of manufactured goods would increase by 444 percent, while U.S. exports of selected agricultural products would increase by 155 percent from their 2010–13 levels. Exports of manufactured goods would increase more than those of agricultural products because U.S. restrictions generally impose much higher trade costs on manufactured goods. The results also indicate that in the absence of U.S. restrictions, there would be substantial new trade in many industries in which there is little to no trade currently, such as non-food manufactured goods. According to the model results, most of this new trade would be the result of trade diversion, increasing U.S. exports to Cuba while reducing exports to Cuba from its other trading partners.

USDA’s Economic Research Service (2015) noted the potential for an expansion in rice trade: “Rice, lard, pork, and wheat flour were the four leading U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba in terms of value during FY 1956–58. Cuba was typically the largest commercial market for U.S. long-grain rice exports prior to the embargo, often taking more than half of U.S. annual long-grain sales and almost one-third of total U.S. rice exports (Efferson, 1952: 518–521; USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service, 1956: 16). If Cuba imported the same amount of rice today as it did then, it would be the 7th leading destination for U.S. rice exports, even though Cuba’s annual per capita rice consumption was about two-thirds of what it is today.”33

All of the benefits identified by these reports implicitly make the case for territorialization, which would also eliminate trade barriers with the U.S. However, territorialization would go much farther towards solving Cuba’s principal economic problem: the inability of the central government and Cuban judiciary to commit to respecting private property rights.34 The Cuban government has de jure recognized private property as a form of ownership in its constitution since 2019. However, this is de facto undercut by Article 30 of the same constitution, which provides that property held by natural and non-state legal persons alike is regulated by the state, which guarantees the redistribution of wealth with the goal of “maintaining the socialist principles of equity and social justice.”35 All of the expected gains in economic activity arising from freer trade are considerable underestimates of the trade benefits arising from territorialization given the expected gains in Cuban productivity that would arise from more secure property rights under the U.S.’s aegis.

On the American side, there are three primary legislative sources of export controls. They are the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 (CDA), the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996 (Libertad or Helms-Burton Act), and the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (TSRA). For Cuban exporters, the State Department maintains limited exemptions under its Section 515.582 list for “goods produced by independent Cuban entrepreneurs, as demonstrated by documentary evidence, that are imported into the United States.” For American exporters, the provisions of TSRA specifically delegated authority to establish procedures to exempt agricultural products from normal licensing requirements. The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) implements this authority via the list of License Exception Agricultural Commodities (AGR).

TSRA provisions authorize the export and re-export of U.S.-origin agricultural commodities under AGR as long as exportation occurs under a written contract and takes place within a year of signing the contract. However, the use of U.S. aid or the use of any government funds to support these exports to Cuba is prohibited. Payments have to be made through cash-in-advance or through third country agreements. U.S. government agencies are prohibited from providing export marketing assistance, technical trade assistance, and credit or credit guarantees for exports to Cuba. This means that the Market Access Program and the Foreign Market Development Program, two of USDA’s signature initiatives, are not applicable. Existing agricultural exports from U.S. to Cuba originate almost entirely from Tampa and Miami. U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, a pro-Cuban business lobby, attempts to document all such exports.36 Total export value averages about $365 million a year, and is concentrated in poultry, corn and soybeans.

Paths to Territorialization

This paper considers three options for territorialization: debt diplomacy, military engagement, and providing support for a domestic democratic revolution. These are not mutually exclusive, but nonetheless debt diplomacy is most preferred for reasons described below.

Military Engagement

Every U.S. simulation of an amphibious invasion since the Cuban missile crisis has concluded that the U.S. military could overcome the Cuban military and topple the Castro regime.37 Major challenges throughout the Cold War centered around Soviet retaliation, e.g. the seizure of Berlin.38 These challenges are now moot. Instead, the major drawback arising from this option arises from potential backlash from the Caribbean and Latin America as well as the U.S. population’s low tolerance for military casualties.

Democratic “Color” Revolution

Cuban social media growth has fomented sociopolitical instability.39 The COVID-19 induced lockdowns put severe strain on the Cuban government, which was rocked by antigovernment and anti-austerity protests in 2021. Around 1,000 antigovernment protestors were arrested, the majority of whom were only recently freed.40 The U.S. State Department supported these protestors in the hopes that they would lead to the overthrow of the Castro regime.41 As discussed more extensively in the Appendix, Cuba has adopted social media monitoring technologies from the PRC to head off this possibility.

Debt Diplomacy

Cuba left the International Monetary Fund in 1964 and is therefore ineligible for the IMF’s lending program. As a result of the Cuban government’s fecklessness, they have proven unable to secure long-term or stable financing. The U.S. could attempt to exploit this by offering Cuba a loan of $40 billion for infrastructure, natural resource development, and liberalization with a 6% percent interest rate. This is far below the global competitive lending rate and the offer would (correctly) be perceived as extremely generous. However, Cuba has proven unable to meet debt obligations. If Cuba liberalized sufficiently, it is likely to prove capable of meeting its debt commitments and generating many of the benefits from territorialization described in this paper. Otherwise, the U.S. could justifiably intervene to secure its loan.

Legal Status of Cuban Natives

In the event of a territorial acquisition of Cuba, the obvious question arises as to what legal status the inhabitants of the island should be given, and how to organize the resulting unincorporated territory.

The Immigration and Nationality Act makes a distinction between a “national of the United States” and a “citizen of the United States.” The former are not intrinsically entitled to birthright citizenship under the prevailing interpretation of the Citizenship Clause under the Fourteenth Amendment. In practice, “under current law, only persons born in American Samoa and Swains Island are U.S. non-citizen nationals (INA 101(a)(29) (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(29) and INA 308(1) (8 U.S.C. 1408)).”42 All other territories, including Puerto Rico and Guam, have been included in the geographic definition of the United States under the INA, and therefore are “subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.” INA 101(a)(38) (8 U.S.C. 1101 (a)(38)) provides that “the term ‘United States,’ when used in a geographical sense, means the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands of the United States.” Nevertheless, territories are not states (they are unincorporated as opposed to incorporated, in the parlance established by the Insular Cases), and so territorial citizens lack voting rights. However, they can move and acquire residency in the continental United States, attaining voting rights by that means. The State Department clarifies that “Nationals of the United States who are not citizens owe allegiance to the United States and are entitled to the consular protection of the United States when abroad, and to U.S. documentation, such as U.S. passports with appropriate endorsements.”43

American Samoa offers a unique situation in being an unincorporated territory (an “outlying possession” according to 8 U.S.C. 1408) with its own autonomous immigration system, and its inhabitants being non-citizen nationals without entitlement to birthright citizenship. This situation was upheld by the D.C. Circuit in the case of Tuaua v. United States (2015). The Court held that “Even assuming a background context grounded in principles of jus soli, we are skeptical the framers plainly intended to extend birthright citizenship to distinct, significantly self-governing political territories within the United States’s sphere of sovereignty—even where, as is the case with American Samoa, ultimate governance remains statutorily vested with the United States Government.”44

Indeed, the Court went so far as to argue that “imposing citizenship” would go against the majoritarian will and customs of the Samoan people: “Despite American Samoa’s lengthy relationship with the United States, the American Samoan people have not formed a collective consensus in favor of United States citizenship. In part this reluctance stems from unique kinship practices and social structures inherent to the traditional Samoan way of life, including those related to the Samoan system of communal land ownership. Traditionally aiga (extended families) ‘communally own virtually all Samoan land, [and] the matais [chiefs] have authority over which family members work what family land and where the nuclear families within the extended family will live.’ King, 520 F.2d at 1159. Extended families under the authority of matais remain a fundamentally important social unit in modern Samoan society.”45

American Samoa was acquired in 1900 by means of an instrument of cession through which the tribal chiefs pledged their loyalty to “an accredited representative of the Government of the United States of America in the Islands,” but otherwise reserved their customary rights. No other territory has been acquired through such a legal instrument, but it is plausible that a petition or referendum could serve as a Cuban equivalent. Nonetheless, it would be a trivial matter of statutory classification to designate Cuba as an “outlying possession,” thereby excluding it from INA’s definition of “the United States.” This would make Cuba the third such outlying possession after American Samoa and the Swains Island.

Otherwise, an alternative model is provided by Guam. Here, the territory is governed by an Organic Act instituted by Congress. Guamanians are citizens by birth, since Guam is listed as part of the geographical definition of the “United States” in Section 101 (a)(38) Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Section 301(a) INA provides that a person born in and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States shall be a U.S. citizen (8 FAM 302.3-1).46

The Organic Act of Guam essentially incorporates the Bill of Rights into the territory via a Congressional and not Constitutional channel.47 It then proceeds to establish Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches analogous to those of a U.S. state. The Governor and Lieutenant Governor are elected officers. Formerly, it used to be the case that the Department of the Interior appointed them—and the same could be done for a territorial Cuba. The legislature is directed to establish a merit system for appointments. An Inspector General in the Interior Department is entrusted to perform independent audits of territorial finances. In essence, it is a surrogate constitution, which allows for considerable leeway in institutional design.

Towards a Grand Strategy for the Western Hemisphere

The Monroe doctrine declared that the Western hemisphere was, “. . . henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers” but was eventually broadened by Theodore Roosevelt to encompass the U.S.’s right to intervene in Latin America and the Caribbean. By declaring his intent to secure the Panama Canal and Greenland for the U.S. over the next four years, President Trump’s endorsement of a “new Monroe Doctrine” has made the implicit policy commitments underlying original Monroe doctrine explicit.48 The new Monroe Doctrine heralds a global environment more receptive to realpolitik.49

Policymakers embracing a new Monroe doctrine risk making strategic errors without an underlying grand strategy. The articulation of an explicit grand strategy for the Western hemisphere would reduce policy incoherence and prevent future policy errors.50 Outlining such a grand strategy is outside the scope of this report, but it would surely include the prevention of adversaries from stationing conventional, nuclear, and intelligence forces within range of the U.S. mainland, crime control in Latin America, and reducing reliance on our adversaries for natural resources. A commitment to the territorialization of Cuba advances all of these objectives and should therefore be the cornerstone of a grand strategy for the Western hemisphere.

–

Appendix: Historical Background

Cuba’s economic and political dependence on the United States was nearly continuous until the Cuban Revolution, coming to an end circa 1959 with the revolutionary government’s nationalizations and expropriations. Even so, the decline in American influence is most self-imposed by embargoes that hamper the export-competitiveness of American firms and prevent the exploitation of significant natural resource reserves.

Cuban–American Relations before the Cold War

In the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898, U.S. policy consisted of two principles. On one hand, a congressional resolution known as the Teller Amendment excluded annexation, resolving that “the United States hereby disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction, or control over [the Island of Cuba] except for the pacification thereof, and asserts its determination, when that is accomplished, to leave the government and control of the Island to its people.” On the other hand, the subsequent Cuban–American Treaty of Relations of 1903 implemented the Platt Amendment of 1901, which gave the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuba to protect its independence and, most importantly, maintain a government that could safeguard fundamental rights.51 Specifically, Treaty reserved that, “The Government of Cuba shall never enter into any treaty or other compact with any foreign power or powers which will impair or tend to impair the independence of Cuba” and “The Government of Cuba consents that the United States may exercise the right to intervene for the preservation of Cuban independence, the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty.”52

Subsequent U.S. foreign policy towards Cuba has vacillated uneasily between these two principles: the principle of Cuban sovereignty and the U.S.’s right to intervene. The United States exercised its right of intervention on numerous occasions in response to demand from Cuban political elites and contested elections. The U.S. intervened in 1906, 1917 and again in 1933. The last intervention was overseen by Secretary of State Sumner Welles to overthrow dictator Gerardo Mechado. The 1934 “Good Neighbor” Treaty revised the 1903 Treaty, abrogating the intervention clause, but retaining Guantanamo Bay.53

Even prior to these political developments, the plurality of Cuba’s exports were destined for the United States. It is estimated that “by the 1880s the US consumed most of Cuba’s exported sugar, tobacco, cacao, coffee, tropical fruits, and nuts; US exports in return were cereals, meats, manufactured goods, condensed milk, vegetable oils, cheese, and fuel. . . . The US imported all of Cuba’s copper production, about a quarter of US copper imports.”54 By 1893 half of Cuba’s cultivated land was devoted to sugar plantations. The United States accounted for half of foreign direct investment in Cuba circa 1914. 84% of US grapefruit imports were sourced from Cuba by 1922, the result of tariff reductions.

The First Marxist-Leninist State in the Western Hemisphere

Relationships between the U.S. and Cuban governments were warm until the late 1950s. Three factors pushed the Eisenhower administration away from the dictatorial Batista government starting in 1957. First, U.S. officials were wary of supporting a regime that was perceived as brutal and corrupt.55 The Eisenhower administration came under increasing pressure from journalists and members of Congress to impose an arms embargo.56 Second, throughout the 1950s the Batista government was mired in escalating guerilla warfare. The U.S. Embassy in Havana and State Department did not believe that Batista could ultimately overcome Fidel Castro’s “26th of July” movement. Third, policymakers believed that by distancing themselves from the Batista regime they could maintain influence in the region.57 Thus, the U.S. government initiated an arms and partial trade embargo on the Batista regime in 1958. Even before the embargo, the CIA provided clandestine but token support for Castro’s 26th of July anti-Batista movement by shipping armaments valued at about $500,000 in contemporary terms from late 1957 to mid-1958.58

Throughout the conflict with Batista, Fidel Castro was publicly ambivalent towards the existing Communist front in Cuba, the Partido Socialista Popular (PSP). A combination of Communist sympathizers in Fidel Castro’s inner-circle, especially his brother Raul Castro, assistance from the PSP in later stages of the Civil War, Soviet diplomacy, and the failed Bay of Pigs operation—detailed below—led to Cuba’s refoundation in December 1961 as a Marxist-Leninist state.59 Soviet diplomatic measures began with the shipments of arms starting in 1959 and large sugar purchases. These purchases largely neutralized the economic impacts of trade restrictions imposed by the Eisenhower administration as retaliation for Cuban nationalizations in October 1960.

Relations between the U.S. and Castro’s Cuba reached their nadir in April 1961 when 1,400 Cuban exiles attempted to overthrow the Castro regime. The U.S., alarmed by ongoing Soviet diplomatic efforts, the large number of Communist sympathizers in the Cuban government, and Cuban nationalizations, armed the exiles but, wishing to maintain plausible deniability, provided no air support. As a result, they were strafed by the Castro regime’s air force upon landing in Cuba and were subsequently captured or killed. The Soviets exploited the failed operation to ship anti-aircraft batteries, advisers, and atomic weapons to Cuba. Alarmed by the declaration of a Marxist-Leninist state in the Western hemisphere, the Kennedy administration declared a complete embargo in February 1962 by Executive Order.60

On October 14th, 1962, a U-2 reconnaissance flight over western Cuba detected ballistic missile installations capable of launching “decapitation strikes” on Washington, D.C. and other major U.S. cities. The Kennedy administration responded by convening the Executive Committee of the National Security Council the next day. Three options were considered: a full-scale military invasion, air strikes, or a naval blockade. A naval blockade (described as a “quarantine”) was launched on October 22nd and high-level negotiations between Soviet premier Khruschev and Kennedy were conducted from October 16th to October 28th.61 These negotiations led to the Kennedy administration openly pledging never to invade Cuba and secretly withdrawing U.S. Jupiter missiles from Turkey in exchange for the removal of missile installations.62

Following the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, Cuba became overwhelmingly dependent on sugar exports to the Soviet Union (sold at below-market prices) in exchange for oil. After the collapse of the USSR, the Cuban economy continuously deteriorated until the early 2000s. Subsequently, the Cuban government found a lifeline in the form of below market price shipments of Venezuelan crude oil. The situation has continued to deteriorate since the COVID-19 pandemic. Energy blackouts are now a routine occurrence, in part due to shortages of fuel imports, and in part due to replacement of thermoelectric power with diesel generators, wind and solar.63 From 1962 onwards, emigration levels from Cuba to the U.S. have been high. For instance, approximately 1% of the population left in the 1980 Mariel boatlift. The post–COVID-19 period has seen this trends intensify beyond all previous limits: approximately 10% of the Cuban population emigrated in the last 3 years.64

Cuba Today: A Gateway for America’s Adversaries

Cuba continues to maintain close relations with Russia, Venezuela, and China. Russia appears to have recently lost interest in the use of Cuba as a base of operations in the Western hemisphere outside of symbolic displays of anti-American solidarity. Russia continues to send the occasional military delegation to Cuba. Cuban ports are, at most, only occasionally used for resupplying Russian warships.65 On the other hand, Chinese and Cuban cooperation appears to have deepened over the same period.66 The Center for Strategic and International Studies believes that China has developed “sophisticated listening posts” capable of obtaining signals intelligence (SIGINT) across the Southeastern U.S.67 Huawei, TP-Link, and ZTE have constructed much of Cuba’s modern telecommunications infrastructure, which has the dual purpose of improving Cuban internet access while maintaining the current Cuban regime’s sociopolitical control.68 Chinese advisors continue to play a key role in Cuba’s fledgling attempts at economic modernization.69

The Cuban–Venezuelan strategic alliance has much deeper foundations than economic exchange in subsidized oil (about 55,000 barrels per day, sometimes declining to 27,000 in crisis situations). Venezuela takes steps to conceal the extent of its cooperation with Cuba. For instance, PDVSA, the Venezuelan state oil company, spoofs the transponder signals from its tanker ships to disguise their movement into Cuba.70 Cuba sends significant volumes of their educated elite (medical workers, educators, military and intelligence officials), on the order of 30,000–50,000, to Venezuela. Although this is one source of hard currency for the Cuban regime, this exchange’s primary purpose appears to be revitalizing the Cuban government’s revolutionary “anti-imperialist” credentials, which stagnated after the collapse of the USSR. In that sense, Venezuela is Cuba’s new Angola.71 The close alliance between Cuba and Venezuela was the proximate cause of Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism by the Trump administration in 2021 and again in 2025.72 Unsurprisingly, attempts at easing relations with Cuba in the Obama administration starting in 2014 resulted in little long-term improvement in Cuban–American relations. For instance, the Obama administration eased restrictions on “people-to-people” educational travel for Americans who wished to visit Cuba in 2014, but this decision was reversed by the Trump administration in 2019. Diplomatic relations were reestablished in 2015, but have resulted in essentially no liberalization by the Cuban regime.

Hugo Chavez, who came into power in 1999 amid a “pink wave” of left-wing Latin American populism, visited Cuba at least 24 times in the decade thereafter. In 2007, he declared that Cuba and Venezuela were “one nation” and that “at heart, we are one government.”73 Chavez’s successor Nicolas Maduro has maintained the same ideological credentials and connections to Cuba. A 2019 investigation by Reuters revealed that Cuban advisors are heavily involved in Venezuela’s Directorate General of Military Counterintelligence, which serves a commissar-like role in surveilling the Venezuelan armed forces for any political deviation. It was reported that “once Cuba began training DGCIM personnel, the intelligence service embedded agents, often dressed in black fatigues, within barracks. There, they would compile dossiers on perceived troublemakers and report any signs of disloyalty.” Phone lines of senior commanders are tapped, and crackdowns have led to at least 300 arrests of military officials. Most of the training took place at the Comandante Arides Estévez Sánchez Military Academy in western Havana.74

–

-

Kurth, J., 1996. “America’s Grand Strategy: A Pattern of History.” The National Interest, (43), pp. 3–19. ↩

-

Richard Hanania. Public Choice theory and the illusion of grand strategy: How Generals, weapons manufacturers, and foreign governments Shape American Foreign Policy. (Routledge, 2021). ↩

-

Piccone, T., 2017. US-Cuba Normalization: US Constituencies for Change. IdeAs. Idées d’Amériques, (10). ↩

-

https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/07/21/about-the-survey-78/ ↩

-

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/biden-administration-cuba-state-sponsor-terrorism-designation-rcna187661 ↩

-

https://www.cbsnews.com/miami/news/trump-reinstates-cuba-as-state-sponsor-of-terrorism-reversing-bidens-decision/ ↩

-

Harper’s. October 1897 Issue. The strategic features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. by A.T. (Alfred Thayer) Mahan. ↩

-

La Orchila Island, Venezuela is approximately 1,500 miles from Florida and only about 445 miles south of Puerto Rico. ↩

-

“Press review: Russia to set up Caribbean base and meet Israeli brass to discuss Iran.” TASS. December 12, 2018. https://tass.com/pressreview/1035596. Cited in: “Dangerous Alliances: Russia’s Strategic Inroads in Latin America” by Douglas Farah and Marianne Richardson. INSS Strategic Perspectives No. 41. 2022. ↩

-

“China’s Intelligence Footprint in Cuba: New Evidence and Implications for U.S. Security.” CSIS. Dec 6, 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-intelligence-footprint-cuba-new-evidence-and-implications-us-security ↩

-

“China, Cuba vow to support each other’s core interests.” China Military Online. Apr 16, 2024. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/CMC/News_209224/16304139.html ↩

-

Gulley AL, Nassar NT, Xun S. China, the United States, and competition for resources that enable emerging technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Apr 17;115(16):4111-4115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717152115. ↩

-

Because Cuba falls under USSOUTHCOM’s area of responsibility, territorialization would relieve much of the U.S.’s defense burden in the Caribbean and free up resources for a pivot to Asia. ↩

-

“‘China is not Cuba’s sugar daddy’: ties between communist nations weaken.” Financial Times. Oct 13, 2024. https://www.ft.com/content/9ca0a495-d5d9-4cc5-acf5-43f42a9128b4 ↩

-

Mentioned in e.g. The Cuban Military and Transition Dynamics; Author, Brian Latell; Publisher, Institute for Cuban and Cuban–American Studies, University of Miami, 2003. https://0201.nccdn.net/1_2/000/000/134/f5b/BLatell.pdf ↩

-

https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2016/07/260396.htm ↩

-

https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/01/267007.htm ↩

-

Latell, 2003. Ibid. ↩

-

“Security Cooperation with Cuba: The Impact of Normalization on the Coast Guard’s Relationship with the Cuban Border Guard.” Derek Cromwell. Naval Postgraduate School. 2021. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1150459 ↩

-

https://www.radiohc.cu/en/especiales/exclusivas/377090-cooperation-between-cuba-and-the-united-states-on-law-enforcement-and-compliance-evolution-results-and-limitations ↩

-

https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/counterterrorism/u-s-removes-cuba-from-list-of-countries-not-fully-cooperating-on-counterterrorism-efforts/ ↩

-

Global demand for cobalt was estimated to be around 215,000 metric tons in 2023. See https://www.iea.org/reports/cobalt ↩

-

Gulley AL, Nassar NT, Xun S. China, the United States, and competition for resources that enable emerging technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Apr 17;115(16):4111-4115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717152115. ↩

-

“Tesla’s battery maker suspends cobalt supplier amid sanctions concern” (July 19, 2018). Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/business/exclusive-teslas-battery-maker-suspends-cobalt-supplier-amid-sanctions-concern-idUSKBN1K92QA/ ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ironically, the Cuban American Nickel Company was about to establish operations in the then-underutilized Moa mine beginning in 1957. This was cut short by Castro’s nationalization in 1960. ↩

-

“Cuba seeks to revive mining sector with new lead and zinc mine” (July 22, 2017). Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/business/cuba-seeks-to-revive-mining-sector-with-new-lead-and-zinc-mine-idUSKBN1A70IN/ ↩

-

H. Michael Erisman. Cuba as a Hemispheric Petropower: Prospects and Consequences. International Journal of Cuban Studies. 2019. Vol. 11(1):43-60. DOI: 10.13169/intejcubastud.11.1.0043 ↩

-

Gebelein, J., 2011. A Geographic Perspective of Cuban Landscapes. Springer, Dordrecht, Heidelberg. ↩

-

Overview of Cuban Imports of Goods and Services and Effects of U.S. Restrictions (Investigation No. 332-552, USITC Publication 4597, March 2016) is available at http://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4597.pdf ↩

-

U.S.-Cuba Agricultural Trade: Past, Present and Possible Future by Steven Zahniser, Bryce Cooke, Jerry Cessna, Nathan Childs, David Harvey, Mildred Haley, Michael McConnell and Carlos Arnade 6/17/2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=35795 ↩

-

Cuba has no independent judiciary. In the absence of bilateral investment treaties it is unlikely to bind itself to the decisions of international tribunals for commercial arbitration. ↩

-

For example, the British investor Amado Fakhre and Canadian entrepreneur Sarkis Yacoubian, were arrested and expropriated of their Cuban holdings in 2011 and 2015, with assets of respectively $17 and $19 million. ↩

-

U.S.–Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. United States Exports To The Republic Of Cuba In 2023. ↩

-

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/30/u-s-planned-261-000-troop-invasion-force-cuba-newly-released-documents-show/813376001/ ↩

-

https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/When%20The%20russians%20Blinked-%20The%20U_S_%20Maritime%20Response%20To%20The%20Cuban%20Missile%20Crisis.pdf ↩

-

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-role-did-the-internet-play-in-fomenting-cuban-protests/ ↩

-

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/cuba-begins-releasing-prisoners-following-biden-announcements-2025-01-15/ ↩

-

https://fightbacknews.org/articles/western-left-intellectuals-and-their-love-affair-attempted-color-revolution-cuba ↩

-

See 8 FAM 300 “US Citizenship and Nationality”: https://fam.state.gov/fam/08fam/08fam030101.html ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Tuaua v. United States, 788 F.3d 300 (D.C. Cir. 2015). https://casetext.com/case/tuaua-v-united-states-1 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

See 8 FAM 302.3 “Acquisition by Birth in Guam on or After December 24, 1952”: https://fam.state.gov/fam/08fam/08fam030203.html ↩

-

48 U.S. Code Subchapter I ↩

-

https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/u-s-monroe-doctrine-hemisphere/ ↩

-

https://www.thenation.com/article/world/trump-latin-america-policy-monroe-doctrine/ ↩

-

For instance, the U.S.’s attempt to overthrow the Maduro government in 2020 failed to account for the loyalty of the military or the high levels of support Maduro would enjoy from most of his neighbors in Latin America and the Caribbean. Such an articulation would exclude further attempts at regime change in Venezuela so long as the material base of Maduro’s power, including his close cooperation with Cuba, remains in place. ↩

-

The treaty was the origin of the lease for the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, which is held by the U.S. to the present day. ↩

-

Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Cuba Embodying the Provisions Defining Their Future Relations as Contained in the Act of Congress Approved March 2, 1901; 5/22/1903; Perfected Treaties, 1778–1945; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/platt-amendment ↩

-

Jorge I. Domínguez, “Conversations among Gentlemen: Elites Frame the US–Cuban Agenda, 1920s–1940s, in Foreign Affairs”, Études caribéennes. http://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/25504; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudescaribeennes.25504 ↩

-

Copeland, Cassandra C. and Jolly, Curtis M. and Thompson, Henry, The History and Potential of Trade between Cuba and the US (March 17, 2011). Journal of Business and Economics, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 163–174, 2011. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1866565 ↩

-

Hugh Thomas, Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), pp. 959–992. ↩

-

Louis A. Pérez Jr., Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), pp. 233–240. ↩

-

Lars Schoultz, That Infernal Little Cuban Republic: The United States and the Cuban Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), pp. 44–48. ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20170123223511/https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90-00965R000706570004-6.pdf ↩

-

Hugh Thomas, Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), pp. 1373. ↩

-

William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornbluh. Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. (The University of North Carolina Press, 2014). ↩

-

Soviet freighters carrying armaments approached, but did not breach, the blockade. ↩

-

Graham T. Allison and Philip Zelikow. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis 2nd ed. (Addison-Wesley, 1999). ↩

-

The Low-Carbon Contradiction: Energy Transition, Geopolitics, and the Infrastructural State in Cuba. By Gustav Cederlöf. Critical Environments: Nature, Science, and Politics. Oakland: University of California Press, 2023. ↩

-

https://www.semafor.com/article/07/24/2024/more-than-10-of-cubas-population-have-fled-amid-a-severe-economic-downturn ↩

-

Robert Evans Ellis. The New Russian Engagement with Latin America: strategic position, commerce, and dreams of the past. (US Army War College Press, 2015). ↩

-

https://apnews.com/article/china-cuba-spy-base-us-intelligence-0f655b577ae4141bdbeabc35d628b18f ↩

-

https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-cuba-spy-sigint/ ↩

-

https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/08/24/cuba-emerges-as-flashpoint-amid-us-china-rivalry/ ↩

-

https://www.ft.com/content/9ca0a495-d5d9-4cc5-acf5-43f42a9128b4 ↩

-

“Venezuela resorts to dark fleet to supply oil to ally Cuba.” Reuters. June 25, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/venezuela-resorts-dark-fleet-supply-oil-ally-cuba-2024-06-25/ ↩

-

“Cuba, Venezuela, and the Americas: A Changing Landscape.” Inter-American Dialogue. 2005. https://www.thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/CubaVenezuelaandtheAmericasAChangingLandscape.pdf ↩

-

“The Footprints of Cuban Intelligence in Venezuela.” Havana Times. Aug 15, 2024. https://havanatimes.org/features/the-footprints-of-cuban-intelligence-in-venezuela/ ↩

-

“Imported repression: How Cuba taught Venezuela to quash military dissent.” Reuters. Aug 22, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/venezuela-cuba-military/ ↩