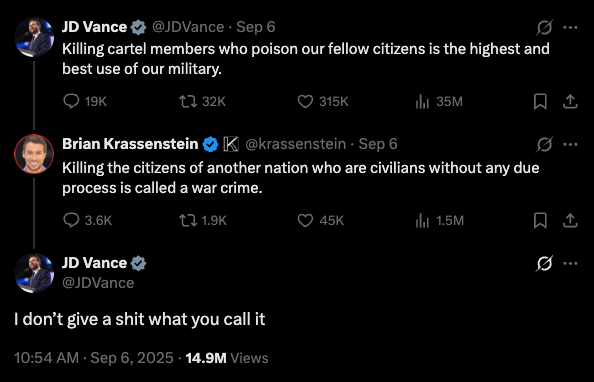

When the Trump Administration blew a cartel drug-running boat to kingdom come on September 2, 2025, critics ensconced in America’s think tanks and papers of record immediately began bleating that the strike constituted a “war crime” or a “violation of the law of armed conflict”. They repeatedly gestured towards the 1973 War Powers Act. The sanctity of INTERNATIONAL LAW was solemnly invoked.

Such protestations ground their criticism in a caricature. International law as usually taught in law schools or IR seminars is essentially Model UN Law - 20th century positive international law codified in the Geneva Convention, UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and similar foundational treaties, as built upon and interpreted by the International Criminal Court and other fora for international lawyers to pontificate. But there is another, more fundamental form of international law that increasingly should guide American action: the Based International Law of the 18th and 19th centuries that actually shaped our Constitution.

And Based International Law permits, nay encourages, killing narcoterrorists on the high seas.

Many Americans rightfully condemn Model UN Law as infringing the sovereignty of the United States. In contrast, American statesmen going back to the very beginning have embraced Based International Law. After all, it’s right there in the Constitution, addressing this very issue.

In Article I Section 8, The Constitution gives to Congress the authority “To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.” But, seperately from public war (i.e. war between states), the Constitution provides Congress the tools to deal with private war in its then most common form: “To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations”.

Offenses Against the Law of Nations

George Washington, the Father of Our Country, was not much for book learning. He preferred hunting, dancing, and gentleman-farming to the life of the mind. So it is notable that in 1789, as our first president, he borrowed a book from the New York Society Library that proved so valuable he never returned it. When trying to understand what the Framers of the Constitution meant by “Offences against the Law of Nations”, you could do worse than to examine that book: Emer de Vattel’s The Law of Nations.

Vattel’s 1758 book, in the classical international law tradition of Grotius, Pufendorf, and Wolff, was well-positioned to become the go-to reference for the Founding Fathers on international law. Besides Washington, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton all referenced and built upon Vattel’s work. So what did Vattel understand to constitute “Offences against the Law of Nations” such as piracy?

For Vattel, the defining feature of crimes like piracy was that they violated the security of all states, preying on vessels regardless of flag or the laws of war. Unlike in wars between states, with pirates there were no sovereigns to entreat or to hold accountable. And by disturbing the peace and failing to follow the laws of nations, they injured not just their victims but all nations. Thus, in combating them, states exercise universal jurisdiction to hold them to account, whenever, wherever, and however they so chose:

Although the justice of each nation ought in general to be confined to the punishment of crimes committed in its own territories, we ought to except from this rule those villains, who, by the nature and habitual frequency of their crimes, violate all public security, and declare themselves the enemies of the human race. Poisoners, assassins, and incendiaries by profession may be exterminated wherever they are seized, for they attack and injure all nations, by trampling under foot the foundations of their common safety. Thus, pirates are sent to the gibbet by the first into whose hand they fall.

Like “outlaws” in the ancient English common law, these enemies of the human race - hostis humani generis - have forfeited all of the usual rights and protections attendant to the citizens of sovereign states. This fundamental condition of enmity extended even to situations otherwise restrained by the law of nations. As Vattel wrote, “Who can doubt that the king of Spain and the powers of Italy have a very good right utterly to destroy those maritime towns of Africa, those nests of pirates; that are continually molesting their commerce, and ruining their subjects?” While piracy has been since antiquity the exemplar of the category, international law has continued to define the category of hostis humani generis, to include not only pirates, poisoners, assassins, and arsonists but also torturers, hostage-takers, and (most notably) terrorists.

To Vattel and our Founding Fathers, it would have been obvious that the fentanyl-smuggling cartels - transnational criminal organizations guilty of piracy, poisoning, assassination, torture, kidnapping, and acts of terrorism - constituted enemies of all mankind engaged in non-state warfare against the United States of America. As hostiles, they are liable to be targeted by violence. As unlawful combatants, they are afforded none of the rights attendant to the soldiers of sovereign states. Based International Law distinguishes actors by their actions, not only by the niceties of the citizenship they might incidentally claim.

Against the Barbary Pirates, for instance, Congress never issued a formal declaration of war - under Based International Law, there was no need to do so - but explicitly authorized six new U.S. Navy frigates for the purpose of “sinking, burning or destroying their ships and vessels wherever you shall find them.” In the era of Based International Law, this right was so obvious that there was relatively little case law. Of the hundreds of times in history where Presidents have ordered the use of military force without asking for permission from Congress, the vast majority of instances were against enemies operating outside of interstate conflict - insurgents, Comanche raiders, pirates, cattle rustlers, terrorists, and criminal gangs, in U.S. territory or beyond it.

Hostis humani generis

Let’s put this in terms that even a New York Times columnist might understand. If a narcoterrorist speedboat was heading towards the United States loaded with explosives or nerve gas intended to conduct a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, even David French would admit the legitimacy of blowing it up on the spot. After all, the narcoterrorists might enter another country’s territory to change vehicles, or factors like weather or operational friction might prevent the U.S. from having another shot at them or interdicting them later.

But the fentanyl smuggled and distributed by cartels kills more Americans a year than every terrorist attack in U.S. history combined. Deaths from fentanyl are now the leading cause of death for Americans age 18-45. Last year, according to provisional data from the CDC, overdoses (primarily caused by fentanyl) killed 80,391 Americans, more than died in the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan combined. If another state were adulterating drugs with fentanyl the way the cartels do, there’s no doubt they would be committing war crimes under the Geneva Convention. Making war on the cartels (already engaged in “predatory war” against the United States) is right and just.

It is incredibly rich for the thinking classes who defended all manner of grotesqueries - George W. Bush’s illegal invasion of Iraq and torture of detainees, Barack Obama’s drone strikes of U.S. citizens and flagrant violation of the War Powers Act in Libya - to be braying about “war crimes” when blowing up transnational criminals on the high seas is a long-standing and unquestioned right of the law of nations, mentioned specifically in the Constitution.

The Trump Administration is right to reject the thin dictates of Model UN Law in order to return to the Based International Law of George Washington and James Madison. Model UN law may have predominated in a comfortable, postwar order of sanitary exchanges between nations – but we have been fooled into imagining that it represents the established historical norm. As the kind of protean, transnational, stateless threats that the cartels represent continue grow in their influence and power over international affairs, so too must America relearn this earlier law of nations.